Wrapped in the Afghan flag and staring down armed Taliban soldiers, Crystal Bayat marched through the streets of Kabul in August 2021, protesting against the return of the extremist group and calling for the preservation of her country's hard-won freedoms.

Her actions put a target on her back.

At just 24, Ms Bayat had never fully experienced living under Taliban rule. Growing up, she had read about the group in books and heard about it from family members, but for her, the Taliban were in the past – and the future was bright.

Before the Taliban returned, Ms Bayat studied in India, eventually returning to Afghanistan to found the think tank Justice and Equality, which focused on civil rights and politics.

A member of the Bayat ethnic group, she also campaigned for improved social and educational inclusion for minorities, and was planning to run for a seat in parliament to represent her community.

“Afghanistan was heaven for me, it was very peaceful – even though we had insecurity and everything, I was living in my house with my family, [I was] with my friends,” she told The National.

“Those were the best moments of my life.”

'Death with dignity is better than a life of humiliation'

US forces began pulling out of Afghanistan in August 2021, with the last soldiers leaving on August 30.

When Ms Bayat heard the news that Kabul would soon fall to the Taliban, she felt a deep sense of betrayal.

“Honestly, [it was] unbelievable,” she said. “Because the international community had been saying before that we could trust them … but because we trusted them, when the Taliban entered Kabul, it was shocking for everyone.

“We could see that our dreams were dying before our eyes.”

As the world held its breath to see what the Taliban would do next, Ms Bayat made a decision.

“It was the second day [after the group's return] when I saw from my window that the Taliban were removing all the women's pictures” from public places, she says.

“And I said to myself, 'No, I have to do something'.”

She called up her friends and asked them to join her in the streets to protest against the Taliban's return on Afghanistan's Independence Day.

“Everyone was like, 'Crystal you are crazy',” she said. “And I'm like, 'What do we have left? We don't have anything. Death with dignity is far better than a life of humiliation'.”

Ms Bayat was one of a handful of female protesters who attended the demonstration in Kabul's city centre, where they demanded the Taliban preserve the rights women and other groups had won since they were last in power.

She said that, although frightened, she felt proud to protest. And then she was interviewed by The New York Times.

Her story spread online, and although many people were supportive, others denounced her, saying she was “against religion, against [Afghan] culture”. Her western-sounding name did nothing to help her case.

While death might bring dignity for her, Ms Bayat came to the chilling realisation that her family would be persecuted as long as the Taliban were in power.

And so they decided to run.

'They're going to kill her'

Thousands of kilometres away, Daniel Druhora, a filmmaker and lecturer in humanitarian innovation at the University of Southern California, was working as part of Digital Dunkirk – an informal global network helping to ferry at-risk Afghans out of the country.

His family history inspired him to join the network, as his father, a pastor and member of a persecuted Christian minority, was able to resettle in the US from post-communist Romania with the help of a Canadian professor.

“Imagine my desk: you have my laptop computers, the screens are full of live maps of Kabul airport and chat boxes on different platforms, one chatting with State Department people, one with military people, CIA agents, one with Afghans trying to escape, NGO people, journalists, photographers,” all sharing information in real time, Mr Druhora said.

Together with some of his students, filmmaking colleagues and other volunteers, he spent hours each day on the phone, writing emails, organising documents – doing everything he could to bring people out, all in absolute secrecy to protect both the evacuees and those helping them on the ground.

“They were the real heroes,” he says. “The soldiers and Afghan allies who risked their lives and careers to rescue others. We were just trying to use our limited knowledge and resources to help the Afghans help themselves.”

Mr Druhora first learnt of Ms Bayat and her need to escape through another person his group was trying to help.

“She is on their [the Taliban's] hit list and she is currently at the airport,” Mr Druhora recalls his contact saying. “Will you speak to her?”

Ms Bayat, he learnt, had few contacts in the West, no US-related documentation, no application for a visa, nothing that could either verify her identity or prove her need to escape.

With the clock ticking, Mr Druhora called another member of the rescue network who was able to draw up a document on a US government letterhead that vouched for Ms Bayat.

Clad in a burqa and carrying her sister's passport out of fear of being recognised at Taliban checkpoints, on Mr Druhora's instructions, Ms Bayat headed to the airport's Abbey Gate, where, days later, a suicide bombing would kill almost 200 people.

Although she says it was difficult to trust a complete stranger, she knew she had no other choice.

The airport was in chaos, with hundreds mobbing the gates trying to present their documents and board planes out of the country.

Mr Druhora was on the phone to Ms Bayat when she shouldered her way to the front of the crowd and shoved her mobile phone in an American soldier's face.

“And she says, 'Speak with Mr Daniel Druhora,' and she puts the speaker on, and I hear, like, 'Yes?'” he says.

“I explained to him [the soldier] very quickly who she was, that she helped organise the protest on August 19 – that they're going to kill her.”

The response was a clipped: “Don't worry, sir. We'll take care of her.”

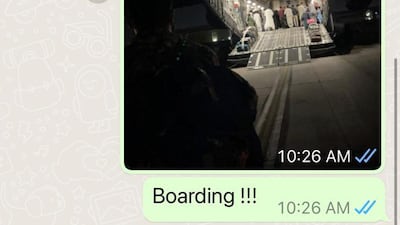

Ms Bayat and her family were soon pulled through the gate, processed and herded on to a plane.

Life after escape

Two years later, Ms Bayat has resettled in Utah, which she says reminds her of home.

“The warm hospitality of the people – it's so much like Afghanistan to me, and I feel peaceful here,” she said.

Although she has found welcome and peace, she yearns for Kabul.

“I miss the library I had in my house. I miss my books. I miss the time that I was spending in cafes with my friends.”

Ms Bayat has been working tirelessly to help other Afghans, in Utah and back home, opening the Crystal Bayat Foundation that focuses on “three Es”: education, evacuation and empowerment.

“My dream is to expand my educational programme in Afghanistan,” she said.

“I really want to help more girls and women who are barred from their jobs and schools, universities. I want my country to be free and see a country where women can work without having fear over their gender and identity.”

She fears for the current state of the Afghan education system, with women and secondary school-aged girls barred from the classroom, and the Taliban's curriculum focusing heavily on indoctrinating pupils with their extreme version of Islam.

Asked if the international community has failed Afghanistan, Ms Bayat is firm.

“The failure in Afghanistan was the failure of the international community because they invested millions and millions of dollars in Afghanistan, spent 20 years in Afghanistan, and they failed,” she says.

“The way they withdrew from Afghanistan was shameful.”

Mr Druhora has stayed in contact with Ms Bayat since her escape.

In November 2021, they met for the first time face to face at USC’s campus at an event Mr Druhora organised, where Ms Bayat was a guest speaker.

“Afghanistan has become the forgotten story,” he said. “When I sat down with her recently, I talked to her about this, like how other crises wiped it out of people's memories, because everybody moved on to the next big fire.

“But she continues to be a voice.”

Ms Bayat's warning to the international community is that Afghanistan is once again becoming a safe haven for terrorist organisations such as Al Qaeda – and that this will have regional and global consequences.

“It's not like people say, what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas,” she says. “What happens in Afghanistan will not stay in Afghanistan.”