For two years British sculptor Piers Secunda has painstakingly worked hard to restore and replicate many of the priceless treasures destroyed by ISIS.

Now an exhibition of his work, Owning the Past: from Mesopotamia to Iraq, has opened at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

ISIS looted and destroyed thousands of ancient artefacts in museums and at the Nirgal Gate, one of several entrances to Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian empire.

One of worst hit areas, was Iraq’s second largest museum the Mosul Museum, which contained ancient Assyrian relics.

The 44-year-old sculptor spoke to The National about the "harrowing" scenes he witnessed when he was confronted with the devastation left behind.

“It was pretty horrendous for me going to the Mosul Museum, there were people who had worked there who had witnessed the arrival of ISIS, their stories were horrifying,” he said.

“It was difficult as an artist to see the damage ISIS had done and take moulds of the damaged sculptures but my job was to make sure we left with these moulds. It was harrowing for me to see what they had done there.

“At one site I had to walk away and compose myself.”

He was commissioned by the Ashmolean to carry out the work and went to Mosul in 2018.

Previously he has carried out similar projects around the world restoring the damage caused by terror groups.

It has taken over a year to restore and replicate more than 600 of the lost treasures in his London studio.

“It has taken years for me to be able to get to the ancient sites because I was unable to go beyond the frontline of ISIS,” he said.

“I think the most important thing is that the Ashmolean gave me the opportunity to make these works using moulds from the broken artefacts.

“There has been no project on this scale and it has been really important to me to expand on the message of the work about the fragility of these artefacts and the culture and value they hold and expose the damage that was done to them when ISIS began systematically targeting them and our history.

“I was worried the pieces would not achieve the emotional impact which I felt and I wanted other people to understand, but I felt a great sense of relief when I managed to do that.”

One of the pieces he worked on contained Sumerian cuneiform script, the world's oldest writing system.

Many of the relics dated from the Sumerian era, one of the first human civilisations whose people lived along the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers some 3,000 years ago.

Sculptures, pottery and cuneiform writing tablets dating from this civilisation were among the works destroyed by ISIS troops.

“Secunda’s work examines some of the most significant subjects of our time – including the deliberate destruction of culture,” a spokesperson for the Ashmolean Museum said.

“His powerful artwork was created by laser scanning and 3D printing a reproduction of the Assyrian relief of a bird-headed spirit that had been removed from the site of Nimrud in the mid-nineteenth century and is now in the Ashmolean.

“Secunda casts the pieces in the installation in industrial floor paint, with the broken stone texture transferred from moulds, which the artist made from the sculptures smashed by ISIS.

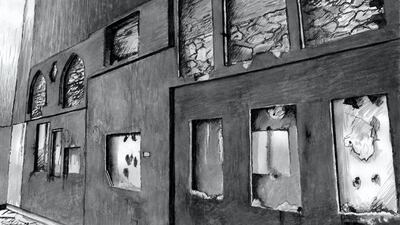

“He used charcoal gathered from the partly burned Mosul Museum to make ink by the traditional process of grinding the charcoal into a powder with a mortar and pestle, mixing it with alcohol and then Gum Arabic. He used this ink to make drawings of the interior of the Mosul Museum, based on photographs, bringing burned remnants of the artefacts and the building back to life as new works of art.”

The full exhibition critically examines the role Oxford University played during the early 20th century in the formation of the nation state of Iraq, previously Mesopotamia, and the importance of the remains of the ancient past in modern cultural identities.

Using a selection of objects, maps and diaries featured in the exhibition, residents from the Middle East reflect on the colonial legacy that continues to have an impact today.

The exhibition looks at the creation of Iraq’s geographic borders and the impact it had on its communities and was inspired by ISIS’ attempts to erase the borders and, with it, the identities of its people and their histories, the museum’s spokesperson said.

Dr Xa Sturgis, director of the Ashmolean Museum, said: “We are proud to present this exhibition which explores this particularly difficult period in Iraq and Oxford’s linked history.

“We are grateful to the local participants who dedicated their time and shared their thoughts and experiences, allowing us to present such an insightful and personal display. Through this and Secunda’s work, the exhibition shows the significant legacy of this pivotal time that still resonates more than a century on and across generations.”

The exhibition runs until May 2021.

Keane on …

Liverpool’s Uefa Champions League bid: “They’re great. With the attacking force they have, for me, they’re certainly one of the favourites. You look at the teams left in it - they’re capable of scoring against anybody at any given time. Defensively they’ve been good, so I don’t see any reason why they couldn’t go on and win it.”

Mohamed Salah’s debut campaign at Anfield: “Unbelievable. He’s been phenomenal. You can name the front three, but for him on a personal level, he’s been unreal. He’s been great to watch and hopefully he can continue now until the end of the season - which I’m sure he will, because he’s been in fine form. He’s been incredible this season.”

Zlatan Ibrahimovic’s instant impact at former club LA Galaxy: “Brilliant. It’s been a great start for him and for the club. They were crying out for another big name there. They were lacking that, for the prestige of LA Galaxy. And now they have one of the finest stars. I hope they can go win something this year.”

The specs

Engine: 1.5-litre turbo

Power: 181hp

Torque: 230Nm

Transmission: 6-speed automatic

Starting price: Dh79,000

On sale: Now

Under 19 Cricket World Cup, Asia Qualifier

Fixtures

Friday, April 12, Malaysia v UAE

Saturday, April 13, UAE v Nepal

Monday, April 15, UAE v Kuwait

Tuesday, April 16, UAE v Singapore

Thursday, April 18, UAE v Oman

UAE squad

Aryan Lakra (captain), Aaron Benjamin, Akasha Mohammed, Alishan Sharafu, Anand Kumar, Ansh Tandon, Ashwanth Valthapa, Karthik Meiyappan, Mohammed Faraazuddin, Rishab Mukherjee, Niel Lobo, Osama Hassan, Vritya Aravind, Wasi Shah

Pharaoh's curse

British aristocrat Lord Carnarvon, who funded the expedition to find the Tutankhamun tomb, died in a Cairo hotel four months after the crypt was opened.

He had been in poor health for many years after a car crash, and a mosquito bite made worse by a shaving cut led to blood poisoning and pneumonia.

Reports at the time said Lord Carnarvon suffered from “pain as the inflammation affected the nasal passages and eyes”.

Decades later, scientists contended he had died of aspergillosis after inhaling spores of the fungus aspergillus in the tomb, which can lie dormant for months. The fact several others who entered were also found dead withiin a short time led to the myth of the curse.

Benefits of first-time home buyers' scheme

- Priority access to new homes from participating developers

- Discounts on sales price of off-plan units

- Flexible payment plans from developers

- Mortgages with better interest rates, faster approval times and reduced fees

- DLD registration fee can be paid through banks or credit cards at zero interest rates

Specs

Engine: Dual-motor all-wheel-drive electric

Range: Up to 610km

Power: 905hp

Torque: 985Nm

Price: From Dh439,000

Available: Now

PROFILE OF STARZPLAY

Date started: 2014

Founders: Maaz Sheikh, Danny Bates

Based: Dubai, UAE

Sector: Entertainment/Streaming Video On Demand

Number of employees: 125

Investors/Investment amount: $125 million. Major investors include Starz/Lionsgate, State Street, SEQ and Delta Partners

Fifa Club World Cup quarter-final

Esperance de Tunis 0

Al Ain 3 (Ahmed 02’, El Shahat 17’, Al Ahbabi 60’)

Quick facts on cancer

- Cancer is the second-leading cause of death worldwide, after cardiovascular diseases

- About one in five men and one in six women will develop cancer in their lifetime

- By 2040, global cancer cases are on track to reach 30 million

- 70 per cent of cancer deaths occur in low and middle-income countries

- This rate is expected to increase to 75 per cent by 2030

- At least one third of common cancers are preventable

- Genetic mutations play a role in 5 per cent to 10 per cent of cancers

- Up to 3.7 million lives could be saved annually by implementing the right health

strategies

- The total annual economic cost of cancer is $1.16 trillion

The Perfect Couple

Starring: Nicole Kidman, Liev Schreiber, Jack Reynor

Creator: Jenna Lamia

Rating: 3/5

COMPANY PROFILE

Founders: Alhaan Ahmed, Alyina Ahmed and Maximo Tettamanzi

Total funding: Self funded

Key findings of Jenkins report

- Founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hassan al Banna, "accepted the political utility of violence"

- Views of key Muslim Brotherhood ideologue, Sayyid Qutb, have “consistently been understood” as permitting “the use of extreme violence in the pursuit of the perfect Islamic society” and “never been institutionally disowned” by the movement.

- Muslim Brotherhood at all levels has repeatedly defended Hamas attacks against Israel, including the use of suicide bombers and the killing of civilians.

- Laying out the report in the House of Commons, David Cameron told MPs: "The main findings of the review support the conclusion that membership of, association with, or influence by the Muslim Brotherhood should be considered as a possible indicator of extremism."

The specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4-cylturbo

Transmission: seven-speed DSG automatic

Power: 242bhp

Torque: 370Nm

Price: Dh136,814

2025 Fifa Club World Cup groups

Group A: Palmeiras, Porto, Al Ahly, Inter Miami.

Group B: Paris Saint-Germain, Atletico Madrid, Botafogo, Seattle.

Group C: Bayern Munich, Auckland City, Boca Juniors, Benfica.

Group D: Flamengo, ES Tunis, Chelsea, Leon.

Group E: River Plate, Urawa, Monterrey, Inter Milan.

Group F: Fluminense, Borussia Dortmund, Ulsan, Mamelodi Sundowns.

Group G: Manchester City, Wydad, Al Ain, Juventus.

Group H: Real Madrid, Al Hilal, Pachuca, Salzburg.

How to register as a donor

1) Organ donors can register on the Hayat app, run by the Ministry of Health and Prevention

2) There are about 11,000 patients in the country in need of organ transplants

3) People must be over 21. Emiratis and residents can register.

4) The campaign uses the hashtag #donate_hope

If you go

The flights

Etihad flies direct from Abu Dhabi to San Francisco from Dh5,760 return including taxes.

The car

Etihad Guest members get a 10 per cent worldwide discount when booking with Hertz, as well as earning miles on their rentals. A week's car hire costs from Dh1,500 including taxes.

The hotels

Along the route, Motel 6 (www.motel6.com) offers good value and comfort, with rooms from $55 (Dh202) per night including taxes. In Portland, the Jupiter Hotel (https://jupiterhotel.com/) has rooms from $165 (Dh606) per night including taxes. The Society Hotel https://thesocietyhotel.com/ has rooms from $130 (Dh478) per night including taxes.

More info

To keep up with constant developments in Portland, visit www.travelportland.com. Good guidebooks include the Lonely Planet guides to Northern California and Washington, Oregon & the Pacific Northwest.

EPL's youngest

- Ethan Nwaneri (Arsenal)

15 years, 181 days old

- Max Dowman (Arsenal)

15 years, 235 days old

- Jeremy Monga (Leicester)

15 years, 271 days old

- Harvey Elliott (Fulham)

16 years, 30 days old

- Matthew Briggs (Fulham)

16 years, 68 days old

RIDE%20ON

%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Larry%20Yang%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStars%3A%20Jackie%20Chan%2C%20Liu%20Haocun%2C%20Kevin%20Guo%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%202%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

AI traffic lights to ease congestion at seven points to Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Street

The seven points are:

Shakhbout bin Sultan Street

Dhafeer Street

Hadbat Al Ghubainah Street (outbound)

Salama bint Butti Street

Al Dhafra Street

Rabdan Street

Umm Yifina Street exit (inbound)

Men’s singles

Group A: Son Wan-ho (Kor), Lee Chong Wei (Mas), Ng Long Angus (HK), Chen Long (Chn)

Group B: Kidambi Srikanth (Ind), Shi Yugi (Chn), Chou Tien Chen (Tpe), Viktor Axelsen (Den)

Women’s Singles

Group A: Akane Yamaguchi (Jpn), Pusarla Sindhu (Ind), Sayaka Sato (Jpn), He Bingjiao (Chn)

Group B: Tai Tzu Ying (Tpe), Sung Hi-hyun (Kor), Ratchanok Intanon (Tha), Chen Yufei (Chn)

Match info:

Wolves 1

Boly (57')

Manchester City 1

Laporte (69')

Volvo ES90 Specs

Engine: Electric single motor (96kW), twin motor (106kW) and twin motor performance (106kW)

Power: 333hp, 449hp, 680hp

Torque: 480Nm, 670Nm, 870Nm

On sale: Later in 2025 or early 2026, depending on region

Price: Exact regional pricing TBA

What sanctions would be reimposed?

Under ‘snapback’, measures imposed on Iran by the UN Security Council in six resolutions would be restored, including:

- An arms embargo

- A ban on uranium enrichment and reprocessing

- A ban on launches and other activities with ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons, as well as ballistic missile technology transfer and technical assistance

- A targeted global asset freeze and travel ban on Iranian individuals and entities

- Authorisation for countries to inspect Iran Air Cargo and Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines cargoes for banned goods

Profile

Company name: Jaib

Started: January 2018

Co-founders: Fouad Jeryes and Sinan Taifour

Based: Jordan

Sector: FinTech

Total transactions: over $800,000 since January, 2018

Investors in Jaib's mother company Alpha Apps: Aramex and 500 Startups

Match info

Liverpool 3

Hoedt (10' og), Matip (21'), Salah (45 3')

Southampton 0

'The Batman'

Stars:Robert Pattinson

Director:Matt Reeves

Rating: 5/5