Live updates: follow the latest news on Russia-Ukraine

One of the best-known residents of Chernobyl’s exclusion zone was Simon, the red fox.

He loved to devour treats thrown in his direction by tourists who, until a week ago, made the two-hour drive north from Kiev to visit the site of one of the world’s greatest man-made disasters.

But with Russian troops now occupying the site, the lives of the region’s animals and the calm they’ve enjoyed for decades is under threat.

On Friday, Ukraine’s State Regulatory Inspectorate reported that radiation levels inside the zone had spiked twenty-fold. Radiation in the area is closely monitored and the increase was due to heavy military vehicles fighting in and around the main reactor site, kicking up radioactive dust.

“In the terrible hands of the aggressor, this significant amount of plutonium-239 can become a nuclear bomb that will turn thousands of hectares into a dead, lifeless desert,” Ukraine’s Ministry of Environmental Protection said in a statement following the takeover.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has said the site was facing another “ecological disaster”, and White House press secretary Jen Psaki expressed outrage about “credible reports” that staff at Chernobyl had been taken hostage by Russian forces.

On Tuesday, Ukrainian observers reported they are no longer able to monitor radiation levels.

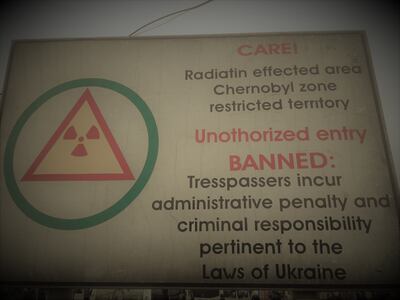

Just as troubling, the road being used by a 64-kilometre-long Russian military convoy runs within a kilometre of the exclusion zone’s main southern checkpoint. Given its strategic location, Chernobyl is likely to remain a significant hotspot for the duration of the conflict.

For more than three decades, a unique ecological experiment has been unfolding inside Chernobyl’s exclusion zone.

Initially, in the weeks and months immediately following the deadly nuclear accident at Reactor 4 in April 1986, most large wildlife in and around the region died from radiation poisoning.

But in the years since, animals of all shapes and sizes have returned.

The 2,634-square-kilometre exclusion zone that reaches the Belarusian border to the north is today home to wolves, bison, boar, deer and herds of wild Przewalski’s horses introduced to the zone in 1998 by researchers.

Dozens of resident and migrating birds such as black storks can be found in the former power plant’s cooling ponds, where fish species such as catfish abound.

Far from being a dead zone, the area, which is about the size of Luxembourg, has thrived in the absence of human activity. So important was the region to researchers and scientists that in 2016 a presidential decree established the Chernobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve inside the exclusion zone.

Experts fear the war may change all that.

The herds of Przewalski's horses, native to Central Asia and extinct in the wild before their release in Chernobyl, may be at particular risk.

“My one concern is the wild horses,” says Maryna Shkvyria, a Kiev-based zoologist who has studied Chernobyl’s growing wolf population for over a decade. “We hope they will not shoot at them.”

With the capital Kiev — about 130km to the south — as Moscow's main target, it’s not clear how large the Russian armed forces footprint will be. What is clear, however, is that scientists' work has been stopped.

“A long-lasting problem may be the implications that this invasion can have for the study and protection of wildlife in the zone,” says Germán Orizaola, a biologist at the University of Oviedo in Spain who has visited the exclusion zone for research work several times a year since 2016.

“All activities from the Chernobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve have stopped, all field research and monitoring from the Chernobyl Centre for Nuclear Safety, Radioactive Waste and Radioecology have stopped, all international collaborations [including mine, with research planned for May] have stopped.

“This may cause a setback of ... recent progress on the study and protection of the rich and diverse wildlife of Chernobyl.”

While the area is not thought to be safe for the return of humans for thousands of years, about 3,000 people have worked inside the exclusion zone, monitoring the facility and building a giant sarcophagus over Reactor 4 that was completed in 2019.

Many workers, who live on site in shifts, are believed to fish in the zone’s waterways and hunt deer.

While people are banned from living in the zone, a small community of locals known as samosely returned to their homes in the weeks and months that followed the disaster and have stayed there ever since.

With the exclusion zone running up against the border with Moscow-allied Belarus — which could reportedly be preparing to enter the war in Ukraine — the region’s unique ecosystem could be under significant threat not only in the short term but for the foreseeable future.