The sharp smell of fuel and gunpowder hung over Tripoli’s old centre.

It was September 2011, three weeks after the Libyan capital fell to rebel forces, and three weeks before its leader Muammar Qaddafi was killed.

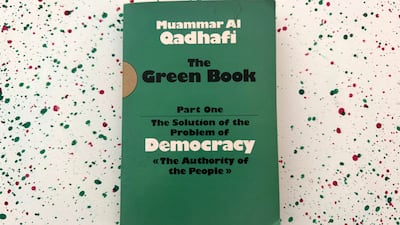

Down a narrow alley near an international hotel, foreign journalists in protective gear filmed as a group of men tossed copies of Qaddafi’s infamous The Green Book into a fire. It wasn’t the first time the book, an economic and social manifesto-turned-collector’s item, had been burned since the uprising began that March. But this was the biggest purge yet, and those present claimed they were watching the last of them go up in flames.

Half a century after its 1975 debut, The Green Book may have vanished from homes and libraries, but its imprint on Libya’s political economy and society endures. The energy-rich country of seven million has spent the past 15 years trying to turn the page. It still hasn’t.

The book’s ideals – collective wealth, direct democracy and local governance – turned toxic long ago. Yet they linger in Libya’s fractured present: a patchwork of armed groups, an oil-fuelled spoils system and populist rhetoric propped up by fragile institutions.

When he introduced The Green Book, Qaddafi declared parliament inherently undemocratic: “The mere existence of a parliament means the absence of the people.” His vision of true democracy meant rule by Popular Committees and the General People’s Congress. Libya, he claimed, was the only real democracy on Earth. “There is no state with a democracy except Libya on the whole planet,” he said.

To spread this doctrine, the regime formed the People’s Establishment for Publication, Distribution and Advertising. The book was printed, translated and plastered everywhere, from schools to taxis, offices and billboards. It became an ideological infrastructure. State media broadcast its teachings. Students memorised passages. Ministry shelves overflowed with green covers. Qaddafi said his proudest achievement was helping Libyans “govern themselves by themselves” through this book.

His product, a rambling mix of political theory, economic advice and lessons on everything from menstruation to home ownership, aimed to be a new universal truth. Rejecting both capitalism and communism, he proposed a “Third Universal Theory” built on grassroots rule. But, as bizarre as the colonel himself, the book often blurred the line between intellect and irony.

In 2008, during a visit to Kyiv dressed in a white safari suit emblazoned with a map of Africa, Qaddafi claimed that Barack Obama’s election in the US had been foretold in his book. “The Green Book says society’s time will come. The Green Book says power will belong to society and its minorities,” he said, speaking from a tent pitched outside the Ukrainian presidential residence.

Despite ruling with an iron fist for more than four decades, Qaddafi fell to a sweeping uprising led in part by exiled Libyans and backed by western powers. Ironically, the rebels embodied perhaps the only principle in The Green Book that ever truly took hold: carrying guns. “If the people are truly sovereign, then they must also be armed. Otherwise, power remains with those who hold the weapons,” Qaddafi argued.

His regime collapsed in 2011. There were hopes that post-Qaddafi Libya, a strategically located country between Africa and Europe and rich in oil and gas, could open up to investment, travel and stability. Instead, militias rushed into the void. Many now function as de facto local authorities, filling the same roles once imagined for Qaddafi’s People’s Committees, only by force, not consent.

These groups mirror his model of decentralised rule, but without legitimacy or oversight. Oil wealth, once promoted as “owned by the people”, now bankrolls warlords. Calls for people-driven governance persist, but the institutions to realise them never emerged.

Even Qaddafi saw the irony: “Theoretically, this is genuine democracy. But realistically, the strong always rule.” He wasn’t wrong. Dictatorship cloaked as direct democracy gave way to chaos draped in similar slogans.

Ask most Libyans what The Green Book meant to them, and they will probably struggle to provide an answer. Centres were once set up across the country to decode the book’s contents, but some say not even Qaddafi understood what he was trying to say.

Today, Libya’s challenges are the same as they were 15 years ago: build durable institutions, distribute wealth fairly and govern by law, not ideology. The Green Book may belong to the past, but its ghost still haunts the present.

In a house in Tripoli’s upscale Andalus neighbourhood, copies of the book remain. Inside a wooden cabinet, tucked in a cardboard box, lie a few faded green covers.

The homeowner told me she saved them when the new government ordered their destruction. Because they were part of history, even if they were meaningless. Because she liked the colour green. Because one day, a collector might pay a fortune to buy them.

She gave me one. It now sits on my shelf among other collectors’ items. Fifteen years on, I’ve only managed to read two pages. But I keep it. A strange little proof that sometimes, madness passes for power.

THE SPECS

Engine: 3.5-litre V6

Transmission: six-speed manual

Power: 325bhp

Torque: 370Nm

Speed: 0-100km/h 3.9 seconds

Price: Dh230,000

On sale: now

Jetour T1 specs

Engine: 2-litre turbocharged

Power: 254hp

Torque: 390Nm

Price: From Dh126,000

Available: Now

Specs

Engine: Dual-motor all-wheel-drive electric

Range: Up to 610km

Power: 905hp

Torque: 985Nm

Price: From Dh439,000

Available: Now

Graduated from the American University of Sharjah

She is the eldest of three brothers and two sisters

Has helped solve 15 cases of electric shocks

Enjoys travelling, reading and horse riding

The National Archives, Abu Dhabi

Founded over 50 years ago, the National Archives collects valuable historical material relating to the UAE, and is the oldest and richest archive relating to the Arabian Gulf.

Much of the material can be viewed on line at the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive - https://www.agda.ae/en

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Specs

Engine: 51.5kW electric motor

Range: 400km

Power: 134bhp

Torque: 175Nm

Price: From Dh98,800

Available: Now

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere

Director: Scott Cooper

Starring: Jeremy Allen White, Odessa Young, Jeremy Strong

Rating: 4/5

TECH%20SPECS%3A%20APPLE%20WATCH%20SERIES%208

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2041mm%2C%20352%20x%20430%3B%2045mm%2C%20396%20x%20484%3B%20Retina%20LTPO%20OLED%2C%20up%20to%201000%20nits%2C%20always-on%3B%20Ion-X%20glass%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Apple%20S8%2C%20W3%20wireless%2C%20U1%20ultra-wideband%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECapacity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2032GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPlatform%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20watchOS%209%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EHealth%20metrics%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%203rd-gen%20heart%20rate%20sensor%2C%20temperature%20sensing%2C%20ECG%2C%20blood%20oxygen%2C%20workouts%2C%20fall%2Fcrash%20detection%3B%20emergency%20SOS%2C%20international%20emergency%20calling%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20GPS%2FGPS%20%2B%20cellular%3B%20Wi-Fi%2C%20LTE%2C%20Bluetooth%205.3%2C%20NFC%20(Apple%20Pay)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDurability%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20IP6X%2C%20water%20resistant%20up%20to%2050m%2C%20dust%20resistant%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20308mAh%20Li-ion%2C%20up%20to%2018h%2C%20wireless%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECards%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20eSIM%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFinishes%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Aluminium%20%E2%80%93%20midnight%2C%20Product%20Red%2C%20silver%2C%20starlight%3B%20stainless%20steel%20%E2%80%93%20gold%2C%20graphite%2C%20silver%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Watch%20Series%208%2C%20magnetic-to-USB-C%20charging%20cable%2C%20band%2Floop%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Starts%20at%20Dh1%2C599%20(41mm)%20%2F%20Dh1%2C999%20(45mm)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Countries offering golden visas

UK

Innovator Founder Visa is aimed at those who can demonstrate relevant experience in business and sufficient investment funds to set up and scale up a new business in the UK. It offers permanent residence after three years.

Germany

Investing or establishing a business in Germany offers you a residence permit, which eventually leads to citizenship. The investment must meet an economic need and you have to have lived in Germany for five years to become a citizen.

Italy

The scheme is designed for foreign investors committed to making a significant contribution to the economy. Requires a minimum investment of €250,000 which can rise to €2 million.

Switzerland

Residence Programme offers residence to applicants and their families through economic contributions. The applicant must agree to pay an annual lump sum in tax.

Canada

Start-Up Visa Programme allows foreign entrepreneurs the opportunity to create a business in Canada and apply for permanent residence.

Silent Hill f

Publisher: Konami

Platforms: PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, PC

Rating: 4.5/5

More coverage from the Future Forum

The Penguin

Starring: Colin Farrell, Cristin Milioti, Rhenzy Feliz

Creator: Lauren LeFranc

Rating: 4/5

GIANT REVIEW

Starring: Amir El-Masry, Pierce Brosnan

Director: Athale

Rating: 4/5

More from UAE Human Development Report:

The 10 Questions

- Is there a God?

- How did it all begin?

- What is inside a black hole?

- Can we predict the future?

- Is time travel possible?

- Will we survive on Earth?

- Is there other intelligent life in the universe?

- Should we colonise space?

- Will artificial intelligence outsmart us?

- How do we shape the future?

Six large-scale objects on show

- Concrete wall and windows from the now demolished Robin Hood Gardens housing estate in Poplar

- The 17th Century Agra Colonnade, from the bathhouse of the fort of Agra in India

- A stagecloth for The Ballet Russes that is 10m high – the largest Picasso in the world

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1930s Kaufmann Office

- A full-scale Frankfurt Kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, which transformed kitchen design in the 20th century

- Torrijos Palace dome

The%20Specs%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ELamborghini%20LM002%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%205.2-litre%20V12%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20450hp%20at%206%2C800rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E500Nm%20at%204%2C500rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFive-speed%20manual%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E0-100kph%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%209%20seconds%20(approx)%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETop%20speed%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20210kph%20(approx)%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EYears%20built%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201986-93%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETotal%20vehicles%20built%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20328%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EValue%20today%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%24300%2C000%2B%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Specs – Taycan 4S

Engine: Electric

Transmission: 2-speed auto

Power: 571bhp

Torque: 650Nm

Price: Dh431,800

Specs – Panamera

Engine: 3-litre V6 with 100kW electric motor

Transmission: 2-speed auto

Power: 455bhp

Torque: 700Nm

Price: from Dh431,800

Indoor cricket in a nutshell

Indoor Cricket World Cup – Sep 16-20, Insportz, Dubai

16 Indoor cricket matches are 16 overs per side

8 There are eight players per team

9 There have been nine Indoor Cricket World Cups for men. Australia have won every one.

5 Five runs are deducted from the score when a wickets falls

4 Batsmen bat in pairs, facing four overs per partnership

Scoring In indoor cricket, runs are scored by way of both physical and bonus runs. Physical runs are scored by both batsmen completing a run from one crease to the other. Bonus runs are scored when the ball hits a net in different zones, but only when at least one physical run is score.

Zones

A Front net, behind the striker and wicketkeeper: 0 runs

B Side nets, between the striker and halfway down the pitch: 1 run

C Side nets between halfway and the bowlers end: 2 runs

D Back net: 4 runs on the bounce, 6 runs on the full

Labour dispute

The insured employee may still file an ILOE claim even if a labour dispute is ongoing post termination, but the insurer may suspend or reject payment, until the courts resolve the dispute, especially if the reason for termination is contested. The outcome of the labour court proceedings can directly affect eligibility.

- Abdullah Ishnaneh, Partner, BSA Law

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

THE CLOWN OF GAZA

Director: Abdulrahman Sabbah

Starring: Alaa Meqdad

Rating: 4/5