The architect behind the design of Dubai Creek Harbour Metro station says the building speaks to the “restless forward momentum” of Dubai.

In an interview with The National, Colin Koop – architect and design partner at acclaimed firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) – outlined the design process of a building set to become not just a train station but Dubai’s next architectural marvel.

It is a story of how dozens of early designs were whittled down to a physical statement that honours Dubai’s rich past and the enduring promise of its future.

“It is a room lit from above that you enter and it somehow resets you … before you enter Dubai Creek Harbour,” notes Mr Koop, who came up with the design concept and led its development. “Which in many ways is the city of the future.”

What is the plan?

SOM is one of the world’s leading design firms, responsible for landmarks as Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, Olympic Tower in New York and Sears Tower in Chicago. Founded in 1936, it has completed more than 10,000 projects in scores of countries around the world.

Dubai's Roads and Transport Authority plan for a metro station in the new neighbourhood of Dubai Creek Harbour intrigued and challenged the company.

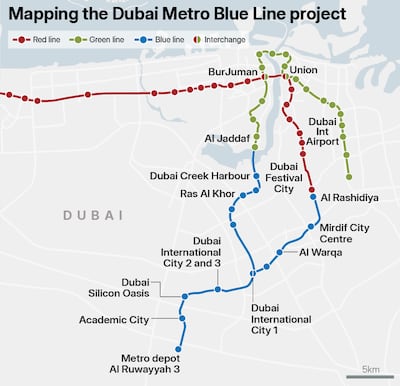

The station is effectively the centrepiece of the Dubai Metro Blue Line. Set to open in 2029, the Blue Line is a gateway to new and expanding neighbourhoods such as Mirdif, International City, Dubai Academic City, Dubai Silicon Oasis and Dubai Creek Harbour.

It also features a bridge soaring across Dubai Creek – itself a historic gateway to Dubai – that carries passengers across the waterway to the station. “You're overlooking the city and riding on an elevated rail line,” he says. “It's already a beautiful cinematic experience.”

Then the Dubai Creek Harbour station appears. Eight bronze jura limestone pieces – four at each side and increasingly taller in size – function as “two hands nearly clasping each other” that rise to a single sheet of glass allowing the building to be lit without artificial lighting for most of the day.

As passengers enter, the station closes in, your world goes from the horizon to a single room and “everything is pointing you up to look at the sky” with light streaming down from the glass ceiling.

The hub is to be named Emaar Properties Station and is one of 14 on the new line. It spans 11,000 square metres, can carry 160,000 passengers a day, soars 74m high and, according to the RTA, is the tallest station in the world.

Speaking from SOM offices in New York, Mr Koop recalls dozens of early designs drawn on trace paper and iPads, and a robust dialogue with the RTA, yet the final design happened to be one of the earliest drawn and “almost drew itself”.

Mr Koop, who is from the US, describes the structure as complicated, especially trying to make the stone sheets rise vertically and stabilise them without turning the building into a cage.

What also sets the project apart is the fact the station is a stop along the line and not a terminal – where multiple trains arrive and depart under a cavernous roof typically at the end of the line. “That was fascinating to us,” says Mr Koop. “It has more stops to make. It's just one of many stations.”

A unique experience

The challenge is to make the arrival and departure experience a moment to rival those grand terminal stations. It aims to do this by a building that is “cleaved in two”, he says, allowing the train to pass through, arriving in the centre on a platform about 40m tall illuminated by the glass ceiling. But when passengers approach the station there is an appearance of little light.

“Then it has this incredible ‘aha’ moment when you walk in and it's just flooded with daylight from above,” he says. “That vault in the centre becomes the grand arrival experience.”

Jura limestone is used to contrast with the steel, glass and metal commonly found across the city. It's a material that's been used in the region for thousands of years and SOM really wanted it to have a “monumental feel to it”.

Stone also helps with the harsh Dubai summer as it absorbs heat, holds it and releases it at night. And at night the station becomes almost like a lantern “lit from within”.

“It has a kind of golden hue to it, so it really does stand again as very serene object in a very frenetic environment,” Mr Koop says.

SOM has been involved in major transport projects across the world, from train halls to airports. Mr Koop is a long-time admirer of the RTA in general “and the idea of taking Dubai beyond the car and trying to make it more walkable”.

The station, for example, provides access to taxis, bus-stops, bike and scooter parking features has pedestrian footbridges. “Most transportation hubs suffer from a kind of maddening confusion,” he says. “Nothing is worse than being stuck in transit in an inhospitable environment.

“Signage is one answer but what you really want to focus on … is using the architecture to queue you to where you need to go effortlessly.”

This is achieved through organisation of the floor or the use of light. Transport projects and the human experience have been central to Mr Koop’s work for decades. Other projects include Moynihan Train Hall in New York, Milano Olympic Village, Italy; and the Moon Village Initiative – a research project for a permanent human lunar base. Yet the Dubai project has been intriguing.

“I think the building is a dialogue on that restless forward momentum of the whole city and the culture and the people,” he says. “And a remembrance of the imprint of the past in choice of the materials and form.

“It's a milestone project for me personally and certainly for SOM and the team that worked on it. I’m incredibly excited to see it constructed.”