One of Abu Dhabi’s newest luxury resorts, The Anantara Santorini hotel, is just 45 minutes from the capital along the E11 motorway, on the coast near Ghanadhah.

But back in 1950 it was a remote and inaccessible spot, almost impossible to visit by vehicles and guarded by sabka, the deceptive mix of sand hardened with gypsum and salt that turned into a quagmire with the first rains of winter.

It was on the beach here, 75 years ago, now overlooked by a five-star replica of a Greek village, that men and machines first arrived by sea to begin Abu Dhabi and the UAE’s journey towards becoming an oil and gas superpower.

Just 20 kilometres away lay Ras Sadr, identified as the first site for drilling by what was then known as Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast), the concession granted by the then Ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Shakhbout bin Sultan.

Sheikh Shakhbout was a patient man, which was fortunate as negotiations to award a concession for oil exploration in the emirate had started nearly two decades earlier.

An agreement had been reached in January 1939, promising the Ruler a lump sum of 300,000 Gulf rupees, the currency of the year, and 100,000 rupees every year until oil was found.

Allowing for inflation, that translates to more than Dh8.32 million for the initial instalment at today’s prices, and Dh2.7 million every year after. Useful income for what was then a poor country, but nothing compared to the riches that would flow along with oil in commercial quantities.

Eight months later, the Second World War broke out, with the oil company representative Basil Lermitte regretfully telling Sheikh Shakhbout that “the company’s exploration programme for this year in Your Excellency’s territory has had to be temporarily abandoned owing to the international emergency”.

“Temporary” turned out to be over a decade, for even when the war ended in 1945, it would be several years before the oil men returned to begin their explorations.

Finally, though, in early 1950 the British political agent in the Gulf was able to report to his superiors in London that “The drilling rig of the Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast) Limited, has already been completed to a height 140 feet (45m) at Ras Sadr (Abu Dhabi territory) and the drilling for oil will be commenced on the 15th”.

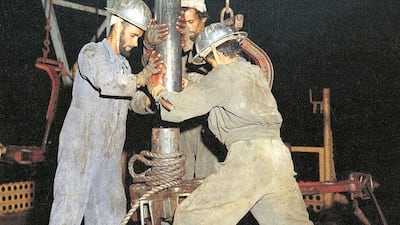

Arriving on barges, equipment was hauled to the site by a fleet of Land Rovers and massive Dodge Power Wagons. For the next 14 months, the giant rig, visible for miles across empty desert, drilled ever deeper. By April, it had become the deepest well in the Middle East at 3,962m – equal to nearly five Burj Khalifa’s stacked on top of each other.

And yet, apparently, it was all for nothing. Only traces of oil were found and nothing to indicate significant quantities. A second well the following year near Jebel Ali also proved dry. It was only in 1958 that oil was finally struck off the coast of Abu Dhabi. The long-promised oil revenue came in 1962.

Gas discovered in Abu Dhabi

Ras Sadr remained a monument to the start, if not the conclusion, of the UAE’s modern economic prosperity. In 1999, a small memorial was created on the drilling site, marked only by a concrete square, in a ceremony attended by three elderly Emiratis who had worked there nearly 50 years earlier.

But as it turns out, Ras Sadr was not quite the failure first thought all those years ago. Last May, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc), made a surprising announcement.

A huge reserve of natural gas reserves had been discovered under the site with the capacity to produce 100 million standard cubic feet every 24 hours - equivalent to produce enough to supply a country of the size of Sweden for an entire day.

How had it not been spotted all those years ago? The answer is the huge advances in technology led by Adnoc, including a 3D mega seismic survey started in 2018, which covered the entirety of Abu Dhabi both on land and offshore.

Interpreting the results of the survey using artificial intelligence and other advanced digital technologies led to the new discovery. Three-quarters of a century ago, hitting natural gas when prospecting for oil had been a dangerous hazard. Just three years after drilling ended at Ras Sadr, drilling a third well at Murban ended in tragedy when poisonous fumes from escaping sour gas caused the deaths of two oil company engineers.

Once considered a nuisance in oilfields that had to be burnt in a process known as flaring, natural gas is now recognised as a valuable resource in great demand, with exports of liquid natural gas (LNG) from the UAE now worth over $7bn (Dh25.7bn) annually.

Today, Ras Sadr stands as a historical landmark and a testament to the UAE’s ability to turn past failures into future successes. What was once dismissed as an unproductive well is now poised to play a crucial role in Abu Dhabi’s energy strategy and serve as a reminder that, in the world of energy, the journey is never truly over.