Squatting on a mattress under a pergola, Ali Araarah said it was only a matter of time before his small Bedouin community of 200 would be evicted to make way for a new Jewish neighbourhood east of Jerusalem.

“There's only one person who can save us,” he said. “Him,” he added as he pointed to the sky above.

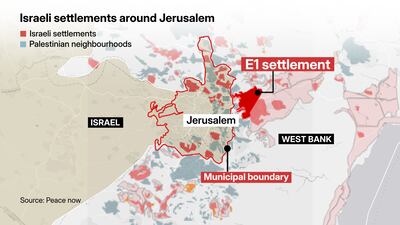

Mr Araarah, a 60-year-old widower and father of 11 children, is an elder of the Kasarat community, one of four in a 12-square-kilometre area known as E1 that Israel plans to develop into a major settlement.

The four communities are part of the Jahalin tribe whose original home is the Negev desert in southern Israel.

The announcement of the plan for the 3,400-home development has caused an international outcry, with critics saying it will divide the occupied West Bank and disrupt the territorial continuity of a future Palestinian state.

Israel agrees. It openly said that the goal is to “bury” a Palestinian state, while also meeting the “natural growth” requirements of nearby Maale Adumim, a settlement built more than 40 years ago that's now home to 44,000 Israelis.

“I don't know where we will go when we leave here, but maybe Israel will find us another place. Only God knows where that is,” said Mr Araarah, who wore a grey robe and a black waistcoat, as he puffed on a cigarette and sipped sweet black tea from a paper cup.

Captured by Israel in the 1967 Middle East war, the occupied West Bank's population includes 700,000 Israeli settlers and 2.7 million Palestinians. Since the Gaza war began nearly two years ago, the area has been under a wave of settler violence against Palestinians and their property, as well as a series of deadly army operations against suspected militants.

Building a Jewish settlement in the E1 area is a project that had been shelved by Israel for decades in the face of international opposition.

Last week, however, the plan received final government approval and construction is expected to start within six months. When completed, it will house about 15,000 people.

That Israel chose to press ahead now with a controversial settlement plan that had long been on ice is seen as the latest evidence of the extremist government's belligerent mood in the face of growing international criticism over its war in Gaza, where it killed more than 62,000 Palestinians and is starving hundreds of thousands, as well the prospect of several major European powers recognising a Palestinian state.

It also speaks to the uncompromising assertiveness of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's government, which has been emboldened by US President Donald Trump's seemingly unrestricted support at a time when many Western powers are beginning to express their deep dismay with Israel.

Illegal projects

Israel's parliament last month voted overwhelmingly in favour of a non-binding declaration to annex the West Bank. It was a symbolic move that, nonetheless, seemed to have further emboldened leaders of the settlement movement and revived calls on the government to do more to strengthen its grip on the area.

Israel Ganz, leader of the West Bank settlement movement and a rising political star, told reporters this week that he has been urging the government to exercise sovereignty over the entire region except areas under direct control of the Palestinian Authority, which he accused of being corrupt and inefficient. If his proposition is embraced, it will place about 70 per cent of the West Bank under direct Israeli rule.

“We will not change what already exists in areas populated by Arabs. We will develop empty [uninhabited] areas,” he said on Tuesday. “We must stop listening to people who tell us what to do,” he added, alluding to international pressure on Israel to stop building settlements in the West Bank.

“The real significance of E1 is to stop the nonsense idea that Jerusalem can be the capital of a Palestinian state."

Later on Tuesday, he hosted a gala dinner for Mr Netanyahu to celebrate the announcement of 17 new West Bank settlements.

“I promised 25 years ago that we would deepen our roots, and we have done so, together,” said the prime minister. “I said we would prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state, and we are doing that, together. I said that we would build and hold fast to our land, our homeland, and we are doing it. And this is not the end – this is the beginning.”

Another settlement leader, Maale Adumim's Mayor, Guy Yifrah, offers a similar sales pitch when he speaks of the E1 development. He told reporters, also on Tuesday, that building illegal settlements allows a “normal life for future generations” and bolsters Israel's security.

A reservist army battalion commander, the mayor of 18 months insists the E1 development would not impede the creation of a Palestinian state, but was quick to state his uncompromising opposition to such an entity.

“I was born here and I want to make sure that the younger generation can continue to live and thrive here,” he said.

"It [the E1 development] will meet the natural growth of Maale Adumim, which needs 800 new housing units every year, something he said it did not have for 20 years,” he claimed as he stood on a ridge with a bird's-eye view of the barren hills that are E1.

No eviction notices yet

The Kasarat community visited by The National this week has lived in the same place by a West Bank motorway for 45 years.

Boasting 400 heads of sheep, it is also home to a large quarry. Its potable water is piped from nearby Palestinian urban centres, although residents complain they only get it late at night.

The caravans they live in are provided by the European Union, and the Palestinian Authority takes children to and from school 5km away by bus.

Unemployment is rife after many lost their jobs in nearby Jewish settlements following Hamas's deadly attack on southern Israel 22 months ago.

The UN food organisation FAO provides the community with fodder for the sheep, and the UN refugee agency UNRWA gives them wheat flour once every three months.

Abdullah Araarah, another one of the community's elders, is taking a dim view of what the future holds for him and his people.

“We haven't received any eviction notices yet, but we expect them along with a demolition order any time,” he said. “When this happens, we will have no land to go to or a home to live in. Only God knows what we will do.”

The predicament and helplessness of his community contrast sharply with the over-assertive and gung-ho attitude of West Bank settlers, whose current defiant mood has chiefly been shaped by the vulnerability Israel had shown on October 7, 2023.

Ariel Greenglick, a 32-year-old settler, runs a goat farm and a restaurant in the occupied West Bank desert near the illegal settlement of Keidar.

A veteran of Israel's wars in Lebanon who served a four-month tour in Gaza last year, he says he set up the farm six years ago to “protect” the spot where his illegal establishment stands as well as the surrounding area, which is the designated site of a new Jewish settlement.

“When my task is done here, I will move elsewhere and do the same,” he said, adding that he was ready to move with his wife and children and settle in Gaza, if they could.