The first whole ancient Egyptian genome has been sequenced by researchers, taken from a man who lived 4,500 to 4,800 years ago in the age of the first pyramids.

By investigating chemical signals in his teeth relating to diet and environment, the researchers showed that the individual was likely to have grown up in Egypt.

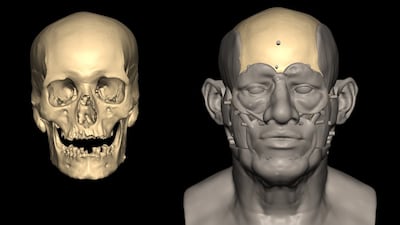

They then used evidence from his skeleton to estimate sex, age, height, and information on ancestry and lifestyle. They found marks which indicate a lifetime of hard labour and signs suggesting he could have worked as a potter or in a trade requiring comparable movements, as his bones had muscle markings from sitting for long periods with outstretched limbs.

His higher-class burial is unexpected for a potter, who would not normally receive such treatment but researchers suggested he may have been exceptionally skilled or successful to advance his social status.

Some 80 per cent of his ancestry was related to ancient people in North Africa and 20 per cent to ancient people in West Asia.

This finding is genetic evidence that people moved into Egypt and mixed with local populations at this time, which was previously only visible in archaeological artefacts.

During this period of ancient Egyptian history, archaeological evidence has suggested trade and cultural connections existed with the Fertile Crescent, particularly the area covering modern Iraq.

Researchers believed that objects and imagery, like writing systems or pottery, were exchanged, but genetic evidence has been limited due to warm temperatures preventing DNA preservation.

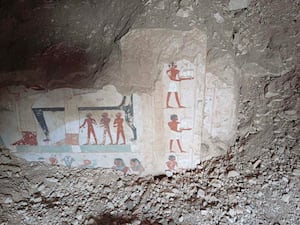

In this study, the research team extracted DNA from the tooth of an individual buried in a ceramic pot in a tomb cut into the hillside in Nuwayrat, a village 265km south of Cairo, using this to sequence his genome. His burial took place before artificial mummification was standard practice, which may have helped to preserve his DNA.

It is the oldest DNA sample from Egypt to date. Forty years ago, Nobel Prize winner Svante Paabo unsuccessfully attempted to extract DNA from people from ancient Egypt, investigating 23 mummies, one of which was a child that he believed could be cloned.

Improvements in techniques led to today’s breakthrough, published in Nature, by researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU).

The burial had been donated by the Egyptian Antiquities Service, while under British rule, to the excavation committee and was initially housed at the Liverpool Institute of Archaeology (which later became part of the University of Liverpool) and then transferred to World Museum Liverpool.

Adeline Morez Jacobs, Visiting Research Fellow at Liverpool John Moores University, said: “Piecing together all the clues from this individual’s DNA, bones and teeth have allowed us to build a comprehensive picture. We hope that future DNA samples from ancient Egypt can expand on when precisely this movement from West Asia started.”

Linus Girdland Flink, Lecturer in Ancient Biomolecules at the University of Aberdeen, said: “This individual has been on an extraordinary journey. He lived and died during a critical period of change in ancient Egypt, and his skeleton was excavated in 1902 and donated to World Museum Liverpool, where it then survived bombings during the Blitz that destroyed most of the human remains in their collection.

"We’ve now been able to tell part of the individual’s story, finding that some of his ancestry came from the Fertile Crescent, highlighting mixture between groups at this time.”

Key facilities

- Olympic-size swimming pool with a split bulkhead for multi-use configurations, including water polo and 50m/25m training lanes

- Premier League-standard football pitch

- 400m Olympic running track

- NBA-spec basketball court with auditorium

- 600-seat auditorium

- Spaces for historical and cultural exploration

- An elevated football field that doubles as a helipad

- Specialist robotics and science laboratories

- AR and VR-enabled learning centres

- Disruption Lab and Research Centre for developing entrepreneurial skills

French business

France has organised a delegation of leading businesses to travel to Syria. The group was led by French shipping giant CMA CGM, which struck a 30-year contract in May with the Syrian government to develop and run Latakia port. Also present were water and waste management company Suez, defence multinational Thales, and Ellipse Group, which is currently looking into rehabilitating Syrian hospitals.

Ukraine%20exports

%3Cp%3EPresident%20Volodymyr%20Zelenskyy%20has%20overseen%20grain%20being%20loaded%20for%20export%20onto%20a%20Turkish%20ship%20following%20a%20deal%20with%20Russia%20brokered%20by%20the%20UN%20and%20Turkey.%3Cbr%3E%22The%20first%20vessel%2C%20the%20first%20ship%20is%20being%20loaded%20since%20the%20beginning%20of%20the%20war.%20This%20is%20a%20Turkish%20vessel%2C%22%20Zelensky%20said%2C%20adding%20exports%20could%20start%20in%20%22the%20coming%20days%22%20under%20the%20plan%20aimed%20at%20getting%20millions%20of%20tonnes%20of%20Ukrainian%20grain%20stranded%20by%20Russia's%20naval%20blockade%20to%20world%20markets.%3Cbr%3E%22Our%20side%20is%20fully%20prepared%2C%22%20he%20said.%20%22We%20sent%20all%20the%20signals%20to%20our%20partners%20--%20the%20UN%20and%20Turkey%2C%20and%20our%20military%20guarantees%20the%20security%20situation.%22%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Ireland (15-1):

Ireland (15-1): Rob Kearney; Keith Earls, Chris Farrell, Bundee Aki, Jacob Stockdale; Jonathan Sexton, Conor Murray; Jack Conan, Sean O'Brien, Peter O'Mahony; James Ryan, Quinn Roux; Tadhg Furlong, Rory Best (capt), Cian Healy

Replacements: Sean Cronin, Dave Kilcoyne, Andrew Porter, Ultan Dillane, Josh van der Flier, John Cooney, Joey Carbery, Jordan Larmour

Coach: Joe Schmidt (NZL)

Ant-Man and the Wasp

Director: Peyton Reed

Starring: Paul Rudd, Evangeline Lilly, Michael Douglas

Three stars

SPEC%20SHEET

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Apple%20M2%2C%208-core%20CPU%2C%20up%20to%2010-core%20CPU%2C%2016-core%20Neural%20Engine%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2013.6-inch%20Liquid%20Retina%2C%202560%20x%201664%2C%20224ppi%2C%20500%20nits%2C%20True%20Tone%2C%20wide%20colour%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%208%2F16%2F24GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStorage%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20256%2F512GB%20%2F%201%2F2TB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EI%2FO%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Thunderbolt%203%20(2)%2C%203.5mm%20audio%2C%20Touch%20ID%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Wi-Fi%206%2C%20Bluetooth%205.0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2052.6Wh%20lithium-polymer%2C%20up%20to%2018%20hours%2C%20MagSafe%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECamera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201080p%20FaceTime%20HD%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EVideo%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Support%20for%20Apple%20ProRes%2C%20HDR%20with%20Dolby%20Vision%2C%20HDR10%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EAudio%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204-speaker%20system%2C%20wide%20stereo%2C%20support%20for%20Dolby%20Atmos%2C%20Spatial%20Audio%20and%20dynamic%20head%20tracking%20(with%20AirPods)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EColours%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Silver%2C%20space%20grey%2C%20starlight%2C%20midnight%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20MacBook%20Air%2C%2030W%20or%2035W%20dual-port%20power%20adapter%2C%20USB-C-to-MagSafe%20cable%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20From%20Dh4%2C999%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Islamophobia definition

A widely accepted definition was made by the All Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims in 2019: “Islamophobia is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness.” It further defines it as “inciting hatred or violence against Muslims”.

RACE CARD

4.30pm: Maiden Dh80,000 1,400m

5pm: Conditions Dh80,000 1,400m

5.30pm: Liwa Oasis Group 3 Dh300,000 1,400m

6pm: The President’s Cup Listed Dh380,000 1,400m

6.30pm: Arabian Triple Crown Group 2 Dh300,000 2,200m

7pm: Wathba Stallions Cup Handicap (30-60) Dh80,000 1,600m

7.30pm: Handicap (40-70) Dh80,000 1,600m.

Cry Macho

Director: Clint Eastwood

Stars: Clint Eastwood, Dwight Yoakam

Rating:**

AT%20A%20GLANCE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EWindfall%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3Cbr%3EAn%20%E2%80%9Cenergy%20profits%20levy%E2%80%9D%20to%20raise%20around%20%C2%A35bn%20in%20a%20year.%20The%20temporary%20one-off%20tax%20will%20hit%20oil%20and%20gas%20firms%20by%2025%20per%20cent%20on%20extraordinary%20profits.%20An%2080%20per%20cent%20investment%20allowance%20should%20calm%20Conservative%20nerves%20that%20the%20move%20will%20dent%20North%20Sea%20firms%E2%80%99%20investment%20to%20save%20them%2091p%20for%20every%20%C2%A31%20they%20spend.%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EA%20universal%20grant%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3Cbr%3EEnergy%20bills%20discount%2C%20which%20was%20effectively%20a%20%C2%A3200%20loan%2C%20has%20doubled%20to%20a%20%C2%A3400%20discount%20on%20bills%20for%20all%20households%20from%20October%20that%20will%20not%20need%20to%20be%20paid%20back.%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETargeted%20measures%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3Cbr%3EMore%20than%20eight%20million%20of%20the%20lowest%20income%20households%20will%20receive%20a%20%C2%A3650%20one-off%20payment.%20It%20will%20apply%20to%20households%20on%20Universal%20Credit%2C%20Tax%20Credits%2C%20Pension%20Credit%20and%20legacy%20benefits.%0D%3Cbr%3ESeparate%20one-off%20payments%20of%20%C2%A3300%20will%20go%20to%20pensioners%20and%20%C2%A3150%20for%20those%20receiving%20disability%20benefits.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The burning issue

The internal combustion engine is facing a watershed moment – major manufacturer Volvo is to stop producing petroleum-powered vehicles by 2021 and countries in Europe, including the UK, have vowed to ban their sale before 2040. The National takes a look at the story of one of the most successful technologies of the last 100 years and how it has impacted life in the UAE.

Read part four: an affection for classic cars lives on

Read part three: the age of the electric vehicle begins

Read part one: how cars came to the UAE

More on animal trafficking

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Russia's Muslim Heartlands

Dominic Rubin, Oxford

The years Ramadan fell in May

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Specs

Engine: Electric motor generating 54.2kWh (Cooper SE and Aceman SE), 64.6kW (Countryman All4 SE)

Power: 218hp (Cooper and Aceman), 313hp (Countryman)

Torque: 330Nm (Cooper and Aceman), 494Nm (Countryman)

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh158,000 (Cooper), Dh168,000 (Aceman), Dh190,000 (Countryman)