The US Navy recently said it had spent at least $500 million shooting down Houthi drones and missiles in the Red Sea, expending 220 missiles, many of which cost several million.

While many of the drones shot down within the 15-month period were hit with cheaper guns – sometimes fired from helicopters – there is a race to slash the cost of intercepting drones – which can cost as little as tens of thousands of dollars.

The Houthis, a rebel group in Yemen, “can rapidly create things that are much simpler than what the United States produces”, former US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said. “They’re not as good, but are certainly good enough to have significant battlefield effect.”

The Houthis' Waid 2 drone, based on the Iranian Shahed-136, is thought to cost at least $50,000, although some estimates put the price tag over $300,000, likely due to supply chain challenges.

Lasers, said to cost a few dollars a shot, have worked in testing in the US and British armed forces, but due to continuing technical challenges, have not been used in combat. The UK, US and China are working on microwave weapons to “fry” drone electronics, but these require large amounts of energy and have short range.

AI-assisted machine guns, like the US Bullfrog, could be the next frontier. But there is a problem: drones are getting cheaper too, and 3D printing could soon play a critical role in the deadly war of price reduction. Already in Ukraine, drones like the 3D-printed, long-range Titan Falcon and the largely 3D-printed Liberator used by rebels in Myanmar are shaping the battlefield, at lower cost that US military drones in the same class.

Worse, cheap decoy drones are often used in Ukraine, while killer drones can fly at high altitude. That makes the slow-moving targets – that normally creep under the radar – easy to spot.

But according to one defence analyst who frequently visits Ukraine, higher flying drones force defenders to use expensive missiles to hit them, rather than cheaper streams of bullets that cannot reach altitude.

At the same time, other drones swarm in low, reducing the available time to intercept them.

3D-printed death

With the spread of 3D printing, these swarms could get easier to build. Other innovations to keep drone costs down include South Korea’s recent Papydrone, made of cardboard, following a similar innovation in Ukraine. But 3D printing offers the prospect of longer flight times and “endurance”.

“You can now print sections of wings for two metres to four metres. Strong materials are available, and the mechanisms for linking them together easily so that they are well integrated exists. But also these 3D printers are coming out with larger beds now. So it used to be you needed a 255mm bed by 255mm but now larger beds are available on printers you can get off the net,” says David Kovar, an expert on drone forensics, the study of armed drones.

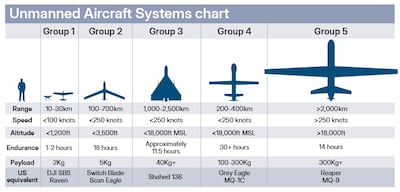

The technology – at least for militias and terrorists – is still in its infancy and mainly used for what the US call Group 1 drones – small quadcopters fitted with bombs. This was on display in Syria, where a lightning offensive by Hayat Tahrir Al Sham used drones with 3D-printed parts that might otherwise be unavailable to a designated terror group, to overwhelm the Syrian army.

For militias, bigger and longer-range systems are coming, although the 3D printing trend here is lagging behind official US and UK efforts, like the Lockheed Martin-funded Firestorm Labs. In Myanmar, rebels have the mainly 3D printed “Liberator” drone that is said to cost about $5,000 with a 40km range.

Several experts have identified 3D printed parts in drones used by Iran, with technology passed on to groups in Iraq and the Houthis in Yemen.

“Even a couple of years ago we were spotting that the battery management system, its casing and other parts had been printed on a fairly large 3D printer for Iran-backed groups. One continuous piece, something to hold all of the batteries within a drone system. So it was things like casings and internal bodywork and structure that we found were being 3D printed,” says Michael Knights, an expert on Iran-backed militias at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

The advantage is clear: when Iran passed Shahed drone technology to Russia with the aim of building 6,000 Geran drones – the Russian variant of the Shahed – for the Ukraine war, there was a delay sending across plans, according to researchers at the Institute for Science and International Security.

In the future, files for 3D printed designs can be sent instantaneously and some Gerans have been found with 3D printed parts, according to the Conflict Armament Research, an NGO. Other delays in the drone production included a lack of skilled workers, something 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, is good at overcoming once people are trained to use the technology.

It allows drone designs to be quickly customised, for example a drone designed to carry a bomb can be modified to carry reconnaissance equipment.

“3D printing is definitely the technology of the future and it’s developing extremely fast. One of the projects I’m working on is looking at 3D printed firearms. To give you an idea of where we might get to with drones, the first 3D-printed firearm was shot in 2013 and it was a single-shot pistol, it could only fire one bullet. Now, 12 years later, people are 3D printing firearms that, if made well are almost as good as commercial firearms,” says Rueben Dass, senior analyst at International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research in Singapore.

While typical 3D printing uses resin, metal printing is also advancing, as well as strong lightweight materials like carbon fibre. Mr Dass and Mr Kovar say that controlling supply chains of dual use technology like printers will pose a headache for those trying to stop it falling into the wrong hands, because, Mr Dass says, of the many “legitimate uses” of the tech.

Last year, the US and UK placed export controls on a range of equipment that can be used for 3D printing metal.

Terror supply chains

Mr Kovar gives Ukraine as an example of how restrictions on exports for equipment used in drones was overcome by both sides. He says this can easily apply to the context of global terrorism.

“Ukraine had to build these supply chains for all sorts of components for everything from the small FPV (first-person view) drones all the way up to these seagoing drones. And they couldn’t buy some of these components from the US because they were ITAR (US International Traffic in Arms Regulations) controlled.”

Mr Kovar, who supports Ukraine in its war against Russia, says China soon filled the supply gap caused by ITAR.

“Because both an allied power, Ukraine, and an adversarial power, Russia, have been forced to develop these ‘just in time’ supply chains for all of the various components they need for drones, those supply chains exist for other people to leverage them. And so if Iran is working with Russia, then that supply chain most likely is also available to the Houthis.”

Autonomous killers

Another aspect worrying researchers is the advent of cheaper “computer vision”, including guidance systems that “match” images of terrain with an on-board computer map to navigate.

It makes them impossible to electronically jam, because they do not need a controlling signal, at least for the last part of their flight.

“Let’s say you want to drop something on critical infrastructure in the US. You fly a drone over to take really high resolution video, or you just go to Google Earth, and Google Earth gives you a four month old 180 degree view of the target. So now you’ve got all the imagery you need, and you can train a Jetson AI system to add to your drone,” Mr Kovar says, referring to the AI system developed by US firm NVIDIA, which was found in Russian autonomous Lancet drones, despite US export restrictions.

“Now you can do image-based navigation, and any GPS jamming or denial defence is going to be invalidated. You don’t need an NVIDIA board for some of these solutions. Raspberry Pi will get the job done,” he says, referring to a widely available microcomputer that can be used for computer vision.

The basic concept of image matching for navigation is decades old, but was once the preserve of big budget US arms programmes.

Mr Dass says we are only at the beginning of these trends, although one challenge for militias and terrorists is that the more capable a drone becomes - longer range, with a bigger weapon or better camera - the more electronics and battery power it needs, adding to the challenge of obtaining the equipment.

“As 3D printing becomes more accessible, and as it becomes cheaper, it definitely opens the door to a lot more opportunities for these groups.

“There’s some reports of Al Shabaab now in Somalia, dabbling with 3D printing. We’ve seen Ukrainians, the pro-democracy forces in Myanmar, who are using 3D printing to to manufacture weapons.

“We have this cycle of knowledge sharing, starting between 2013 to 2019 with ISIS and their use of small drones. The same modus operandi was picked up by the Ukrainians. And from there on, in Myanmar, by the rebels there. And the interesting thing about Myanmar is that the rebels first used it, and then the junta followed them. And now it’s everywhere.”

Iran, according to Mohammed Albasha of the Basha Report, a US-based risk advisory service, has an “advanced UAV industry”.

“Domestic 3D printing capabilities, and reliance on self-sufficiency under sanctions make it plausible for prototyping or manufacturing non-critical components. If this is not happening already, it is likely to occur in the short to midterm future, as the future of warfare increasingly relies on autonomous systems with affordable components.

“However, it is important to note that the Houthis do not rely solely on Iranian drone components; there is documented use of Chinese and German engines and European electronic chips, indicating a global supply chain with built-in redundancies. The Houthis are now capable of mass-producing the Samad series drones independently of Iranian parts, though their long-range drones and ballistic missiles still depend on Iranian supplies and logistical support,” Mr Albasha says.

Yoel Guzansky, a senior researcher and head of the Gulf Program at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) agrees.

“If the Houthis can print drone equipment inside Yemen, it has a lot of geopolitical and strategic effects, because then they are much more independent on their decision making, and they will need Iran less and less. The Houthis have sustained fighting against global powers for almost a year and a half, showing that with very little support and investment by Iran, they can cause a lot of global damage. They will continue to be a security problem for the Red Sea, Bab Al Mandeb – and perhaps for the world.”

Countdown to Zero exhibition will show how disease can be beaten

Countdown to Zero: Defeating Disease, an international multimedia exhibition created by the American Museum of National History in collaboration with The Carter Center, will open in Abu Dhabi a month before Reaching the Last Mile.

Opening on October 15 and running until November 15, the free exhibition opens at The Galleria mall on Al Maryah Island, and has already been seen at the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum in Atlanta, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

How to wear a kandura

Dos

- Wear the right fabric for the right season and occasion

- Always ask for the dress code if you don’t know

- Wear a white kandura, white ghutra / shemagh (headwear) and black shoes for work

- Wear 100 per cent cotton under the kandura as most fabrics are polyester

Don’ts

- Wear hamdania for work, always wear a ghutra and agal

- Buy a kandura only based on how it feels; ask questions about the fabric and understand what you are buying

Tamkeen's offering

- Option 1: 70% in year 1, 50% in year 2, 30% in year 3

- Option 2: 50% across three years

- Option 3: 30% across five years

Tree of Hell

Starring: Raed Zeno, Hadi Awada, Dr Mohammad Abdalla

Director: Raed Zeno

Rating: 4/5

THE SPECS

Engine: 1.5-litre turbocharged four-cylinder

Transmission: Constant Variable (CVT)

Power: 141bhp

Torque: 250Nm

Price: Dh64,500

On sale: Now

The specs: 2017 Ford F-150 Raptor

Price, base / as tested Dh220,000 / Dh320,000

Engine 3.5L V6

Transmission 10-speed automatic

Power 421hp @ 6,000rpm

Torque 678Nm @ 3,750rpm

Fuel economy, combined 14.1L / 100km

Key findings of Jenkins report

- Founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, Hassan al Banna, "accepted the political utility of violence"

- Views of key Muslim Brotherhood ideologue, Sayyid Qutb, have “consistently been understood” as permitting “the use of extreme violence in the pursuit of the perfect Islamic society” and “never been institutionally disowned” by the movement.

- Muslim Brotherhood at all levels has repeatedly defended Hamas attacks against Israel, including the use of suicide bombers and the killing of civilians.

- Laying out the report in the House of Commons, David Cameron told MPs: "The main findings of the review support the conclusion that membership of, association with, or influence by the Muslim Brotherhood should be considered as a possible indicator of extremism."

Major honours

ARSENAL

BARCELONA

- La Liga - 2013

- Copa del Rey - 2012

- Fifa Club World Cup - 2011

CHELSEA

- Premier League - 2015, 2017

- FA Cup - 2018

- League Cup - 2015

SPAIN

- World Cup - 2010

- European Championship - 2008, 2012

The specs

Engine: 1.5-litre turbo

Power: 181hp

Torque: 230Nm

Transmission: 6-speed automatic

Starting price: Dh79,000

On sale: Now

What are the influencer academy modules?

- Mastery of audio-visual content creation.

- Cinematography, shots and movement.

- All aspects of post-production.

- Emerging technologies and VFX with AI and CGI.

- Understanding of marketing objectives and audience engagement.

- Tourism industry knowledge.

- Professional ethics.

Labour dispute

The insured employee may still file an ILOE claim even if a labour dispute is ongoing post termination, but the insurer may suspend or reject payment, until the courts resolve the dispute, especially if the reason for termination is contested. The outcome of the labour court proceedings can directly affect eligibility.

- Abdullah Ishnaneh, Partner, BSA Law

Fund-raising tips for start-ups

Develop an innovative business concept

Have the ability to differentiate yourself from competitors

Put in place a business continuity plan after Covid-19

Prepare for the worst-case scenario (further lockdowns, long wait for a vaccine, etc.)

Have enough cash to stay afloat for the next 12 to 18 months

Be creative and innovative to reduce expenses

Be prepared to use Covid-19 as an opportunity for your business

* Tips from Jassim Al Marzooqi and Walid Hanna

Specs

Engine: 51.5kW electric motor

Range: 400km

Power: 134bhp

Torque: 175Nm

Price: From Dh98,800

Available: Now

Washmen Profile

Date Started: May 2015

Founders: Rami Shaar and Jad Halaoui

Based: Dubai, UAE

Sector: Laundry

Employees: 170

Funding: about $8m

Funders: Addventure, B&Y Partners, Clara Ventures, Cedar Mundi Partners, Henkel Ventures

More from Neighbourhood Watch

The design

The protective shell is covered in solar panels to make use of light and produce energy. This will drastically reduce energy loss.

More than 80 per cent of the energy consumed by the French pavilion will be produced by the sun.

The architecture will control light sources to provide a highly insulated and airtight building.

The forecourt is protected from the sun and the plants will refresh the inner spaces.

A micro water treatment plant will recycle used water to supply the irrigation for the plants and to flush the toilets. This will reduce the pavilion’s need for fresh water by 30 per cent.

Energy-saving equipment will be used for all lighting and projections.

Beyond its use for the expo, the pavilion will be easy to dismantle and reuse the material.

Some elements of the metal frame can be prefabricated in a factory.

From architects to sound technicians and construction companies, a group of experts from 10 companies have created the pavilion.

Work will begin in May; the first stone will be laid in Dubai in the second quarter of 2019.

Construction of the pavilion will take 17 months from May 2019 to September 2020.

Other must-tries

Tomato and walnut salad

A lesson in simple, seasonal eating. Wedges of tomato, chunks of cucumber, thinly sliced red onion, coriander or parsley leaves, and perhaps some fresh dill are drizzled with a crushed walnut and garlic dressing. Do consider yourself warned: if you eat this salad in Georgia during the summer months, the tomatoes will be so ripe and flavourful that every tomato you eat from that day forth will taste lacklustre in comparison.

Badrijani nigvzit

A delicious vegetarian snack or starter. It consists of thinly sliced, fried then cooled aubergine smothered with a thick and creamy walnut sauce and folded or rolled. Take note, even though it seems like you should be able to pick these morsels up with your hands, they’re not as durable as they look. A knife and fork is the way to go.

Pkhali

This healthy little dish (a nice antidote to the khachapuri) is usually made with steamed then chopped cabbage, spinach, beetroot or green beans, combined with walnuts, garlic and herbs to make a vegetable pâté or paste. The mix is then often formed into rounds, chilled in the fridge and topped with pomegranate seeds before being served.

THE%20SPECS

%3Cp%3EBattery%3A%2060kW%20lithium-ion%20phosphate%3Cbr%3EPower%3A%20Up%20to%20201bhp%3Cbr%3E0%20to%20100kph%3A%207.3%20seconds%3Cbr%3ERange%3A%20418km%3Cbr%3EPrice%3A%20From%20Dh149%2C900%3Cbr%3EAvailable%3A%20Now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Learn more about Qasr Al Hosn

In 2013, The National's History Project went beyond the walls to see what life was like living in Abu Dhabi's fabled fort:

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: Mamo Year it started: 2019 Founders: Imad Gharazeddine, Asim Janjua Based: Dubai, UAE Number of employees: 28 Sector: Financial services Investment: $9.5m Funding stage: Pre-Series A Investors: Global Ventures, GFC, 4DX Ventures, AlRajhi Partners, Olive Tree Capital, and prominent Silicon Valley investors. AL%20BOOM

%3Cp%20style%3D%22text-align%3Ajustify%3B%22%3E%26nbsp%3B%26nbsp%3B%26nbsp%3BDirector%3AAssad%20Al%20Waslati%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%20style%3D%22text-align%3Ajustify%3B%22%3E%0DStarring%3A%20Omar%20Al%20Mulla%2C%20Badr%20Hakami%20and%20Rehab%20Al%20Attar%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3EStreaming%20on%3A%20ADtv%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3ERating%3A%203.5%2F5%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Company%20Profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Cargoz%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EDate%20started%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20January%202022%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Premlal%20Pullisserry%20and%20Lijo%20Antony%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2030%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Seed%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

500 People from Gaza enter France

115 Special programme for artists

25 Evacuation of injured and sick

What can victims do?

Always use only regulated platforms

Stop all transactions and communication on suspicion

Save all evidence (screenshots, chat logs, transaction IDs)

Report to local authorities

Warn others to prevent further harm

Courtesy: Crystal Intelligence

Kill%20Bill%20Volume%201

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20Quentin%20Tarantino%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20Uma%20Thurman%2C%20David%20Carradine%20and%20Michael%20Madsen%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%204.5%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Mohammed bin Zayed Majlis

Groom and Two Brides

Director: Elie Semaan

Starring: Abdullah Boushehri, Laila Abdallah, Lulwa Almulla

Rating: 3/5

How green is the expo nursery?

Some 400,000 shrubs and 13,000 trees in the on-site nursery

An additional 450,000 shrubs and 4,000 trees to be delivered in the months leading up to the expo

Ghaf, date palm, acacia arabica, acacia tortilis, vitex or sage, techoma and the salvadora are just some heat tolerant native plants in the nursery

Approximately 340 species of shrubs and trees selected for diverse landscape

The nursery team works exclusively with organic fertilisers and pesticides

All shrubs and trees supplied by Dubai Municipality

Most sourced from farms, nurseries across the country

Plants and trees are re-potted when they arrive at nursery to give them room to grow

Some mature trees are in open areas or planted within the expo site

Green waste is recycled as compost

Treated sewage effluent supplied by Dubai Municipality is used to meet the majority of the nursery’s irrigation needs

Construction workforce peaked at 40,000 workers

About 65,000 people have signed up to volunteer

Main themes of expo is ‘Connecting Minds, Creating the Future’ and three subthemes of opportunity, mobility and sustainability.

Expo 2020 Dubai to open in October 2020 and run for six months

Auron Mein Kahan Dum Tha

Starring: Ajay Devgn, Tabu, Shantanu Maheshwari, Jimmy Shergill, Saiee Manjrekar

Director: Neeraj Pandey

Rating: 2.5/5

The specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 261hp at 5,500rpm

Torque: 405Nm at 1,750-3,500rpm

Transmission: 9-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 6.9L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh117,059

The specs: 2018 Volkswagen Teramont

Price, base / as tested Dh137,000 / Dh189,950

Engine 3.6-litre V6

Gearbox Eight-speed automatic

Power 280hp @ 6,200rpm

Torque 360Nm @ 2,750rpm

Fuel economy, combined 11.7L / 100km

Who are the Sacklers?

The Sackler family is a transatlantic dynasty that owns Purdue Pharma, which manufactures and markets OxyContin, one of the drugs at the centre of America's opioids crisis. The family is well known for their generous philanthropy towards the world's top cultural institutions, including Guggenheim Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, Tate in Britain, Yale University and the Serpentine Gallery, to name a few. Two branches of the family control Purdue Pharma.

Isaac Sackler and Sophie Greenberg were Jewish immigrants who arrived in New York before the First World War. They had three sons. The first, Arthur, died before OxyContin was invented. The second, Mortimer, who died aged 93 in 2010, was a former chief executive of Purdue Pharma. The third, Raymond, died aged 97 in 2017 and was also a former chief executive of Purdue Pharma.

It was Arthur, a psychiatrist and pharmaceutical marketeer, who started the family business dynasty. He and his brothers bought a small company called Purdue Frederick; among their first products were laxatives and prescription earwax remover.

Arthur's branch of the family has not been involved in Purdue for many years and his daughter, Elizabeth, has spoken out against it, saying the company's role in America's drugs crisis is "morally abhorrent".

The lawsuits that were brought by the attorneys general of New York and Massachussetts named eight Sacklers. This includes Kathe, Mortimer, Richard, Jonathan and Ilene Sackler Lefcourt, who are all the children of either Mortimer or Raymond. Then there's Theresa Sackler, who is Mortimer senior's widow; Beverly, Raymond's widow; and David Sackler, Raymond's grandson.

Members of the Sackler family are rarely seen in public.

What drives subscription retailing?

Once the domain of newspaper home deliveries, subscription model retailing has combined with e-commerce to permeate myriad products and services.

The concept has grown tremendously around the world and is forecast to thrive further, according to UnivDatos Market Insights’ report on recent and predicted trends in the sector.

The global subscription e-commerce market was valued at $13.2 billion (Dh48.5bn) in 2018. It is forecast to touch $478.2bn in 2025, and include the entertainment, fitness, food, cosmetics, baby care and fashion sectors.

The report says subscription-based services currently constitute “a small trend within e-commerce”. The US hosts almost 70 per cent of recurring plan firms, including leaders Dollar Shave Club, Hello Fresh and Netflix. Walmart and Sephora are among longer established retailers entering the space.

UnivDatos cites younger and affluent urbanites as prime subscription targets, with women currently the largest share of end-users.

That’s expected to remain unchanged until 2025, when women will represent a $246.6bn market share, owing to increasing numbers of start-ups targeting women.

Personal care and beauty occupy the largest chunk of the worldwide subscription e-commerce market, with changing lifestyles, work schedules, customisation and convenience among the chief future drivers.

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

MATCH INFO

Manchester United 1 (Rashford 36')

Liverpool 1 (Lallana 84')

Man of the match: Marcus Rashford (Manchester United)

'The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey'

Rating: 3/5

Directors: Ramin Bahrani, Debbie Allen, Hanelle Culpepper, Guillermo Navarro

Writers: Walter Mosley

Stars: Samuel L Jackson, Dominique Fishback, Walton Goggins

Race 3

Produced: Salman Khan Films and Tips Films

Director: Remo D’Souza

Cast: Salman Khan, Anil Kapoor, Jacqueline Fernandez, Bobby Deol, Daisy Shah, Saqib Salem

Rating: 2.5 stars

Where to buy

Limited-edition art prints of The Sofa Series: Sultani can be acquired from Reem El Mutwalli at www.reemelmutwalli.com

Silent Hill f

Publisher: Konami

Platforms: PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, PC

Rating: 4.5/5

All you need to know about Formula E in Saudi Arabia

What The Saudia Ad Diriyah E-Prix

When Saturday

Where Diriyah in Saudi Arabia

What time Qualifying takes place from 11.50am UAE time through until the Super Pole session, which is due to end at 12.55pm. The race, which will last for 45 minutes, starts at 4.05pm.

Who is competing There are 22 drivers, from 11 teams, on the grid, with each vehicle run solely on electronic power.

Mubadala World Tennis Championship 2018 schedule

Thursday December 27

Men's quarter-finals

Kevin Anderson v Hyeon Chung 4pm

Dominic Thiem v Karen Khachanov 6pm

Women's exhibition

Serena Williams v Venus Williams 8pm

Friday December 28

5th place play-off 3pm

Men's semi-finals

Rafael Nadal v Anderson/Chung 5pm

Novak Djokovic v Thiem/Khachanov 7pm

Saturday December 29

3rd place play-off 5pm

Men's final 7pm

ABU%20DHABI'S%20KEY%20TOURISM%20GOALS%3A%20BY%20THE%20NUMBERS

%3Cp%3EBy%202030%2C%20Abu%20Dhabi%20aims%20to%20achieve%3A%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%2039.3%20million%20visitors%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20nearly%2064%25%20up%20from%202023%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%20Dh90%20billion%20contribution%20to%20GDP%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20about%2084%25%20more%20than%20Dh49%20billion%20in%202023%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%20178%2C000%20new%20jobs%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20bringing%20the%20total%20to%20about%20366%2C000%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%2052%2C000%20hotel%20rooms%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20up%2053%25%20from%2034%2C000%20in%202023%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%207.2%20million%20international%20visitors%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20almost%2090%25%20higher%20compared%20to%202023's%203.8%20million%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E%E2%80%A2%203.9%20international%20overnight%20hotel%20stays%2C%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2022%25%20more%20from%203.2%20nights%20in%202023%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

F1 The Movie

Starring: Brad Pitt, Damson Idris, Kerry Condon, Javier Bardem

Director: Joseph Kosinski

Rating: 4/5