Live updates: Follow the latest on Syria

The long hallway of the thoracic surgery department of Syria’s Damascus Hospital ends with an unmarked blue door that, until recently, opened only from the inside.

Beyond the door is an extension to the hospital: a medical ward with four hospital rooms and a storage area containing a wealth of anaesthetic, medical tools and medicine not readily found in the rest of the complex. There are no surveillance cameras.

Two doctors and two hospital administration workers who spoke to The National said the mysterious 'Friends Ward' was an open secret no one talked about, that was allocated for the treatment of Iran-backed foreign fighters of various nationalities. An orthopaedic surgeon who said he was called to the ward dozens of times explained that on at least one occasion, high-profile detainees were also treated there in secret.

One administrator, Abu Ahmad, said he worked in the ward for two years and knew its internal workings. “The employees of the ward were Syrian but we weren’t on the hospital's payroll,” he told The National. “We took orders from Syrian State Security and from Iran.”

Doctors on shift would be suddenly called up to the mysterious ward at the far end of the thoracic department. There, they would be ordered to operate on battle-wounded, Iran-supported foreign fighters.

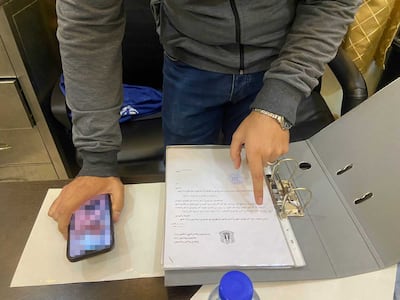

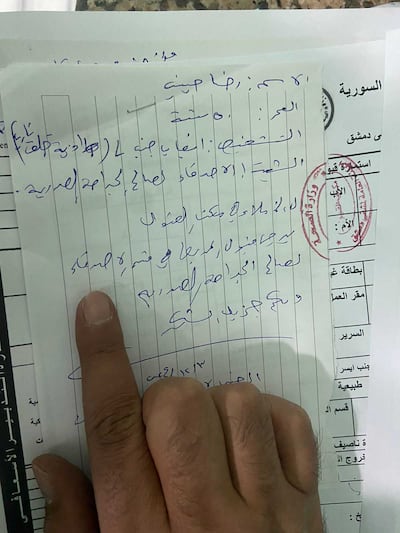

“The last person I operated on was less than two weeks ago and he was named Reda Husseini,” said Dr Majed Jneidi, a thoracic surgeon at the Damascus Hospital. He grabbed Mr Husseini’s file from the ward’s reception desk.

“As you can see, he had a gunshot wound in his left shoulder. They called me into the unit to operate on it.”

Doctors and administrators at the hospital said the foreign fighters who came to the ward were of several nationalities: “Iranian, Afghan, Pakistani, Iraqi and even some Syrian soldiers,” said Abu Ahmad, who had worked as a mid-level ward administrator at the ward for two years. “But even the Syrians who came in weren’t ordinary Syrian army soldiers – they were part of the ‘alternative army’.”

“The ward was named ‘Friends’ because the foreign fighters were considered ‘friends’ of the regime,” he added.

Mr Ahmad was referring to the numerous Iran-backed militias that proliferated during Syria’s civil war, when Shiite foreign fighters and Syrian recruits were contracted into Iranian-sponsored militias in the country. They fought throughout Syria’s civil war – multifaceted and waged with the help of foreign proxies by all vying sides – to prop up the reign of the now-deposed president Bashar Al Assad.

The National did not use Mr Ahmad’s real name out of concern his willing affiliation with the Friends Ward could draw public retribution from those still bitter over the brutal reign of Mr Al Assad. Throughout the war, the former president mobilised his own minority Alawite sect and other Shiite minorities, as well as foreign militias, to prop his regime – fomenting public resentment against a majority Sunni population.

It has been five days since the rule of Mr Al Assad ground to a halt after rebel forces swept into the capital. Since then, the jubilance of the Syrian people at seeing the Assad dictatorship toppled has been replaced with uncertainty and cautious optimism. Major questions hang in the air of a new Syria run by a Sunni opposition: will it be inclusive and tolerant of religious minorities? Will acts of retribution against civilians perceived as loyalists to the old regime be condoned?

Secretly treated

Mr Ahmad’s work mostly involved keeping records of the fighters in a secret reception office downstairs known as the “follow-up room,” where he said financial bills were settled.

“There was a file called ‘the families of the martyrs’, where we kept all the financial records,” he said. "The follow-up office would settle the finances for the injured fighters, and it was funded by Iran."

The National has reviewed documents strewn about the follow-up office and can confirm the existence of a medical registry of foreign names written in Arabic and Farsi. The office was left in disarray when the directors of the Friends Ward fled after the rebels swept into Damascus. Computers and documents were cleared within hours.

A ripped poster of an Iranian martyr lay on the ground in the cluttered room, which appeared to have been quickly evacuated. It was labelled “the honourable Commander-in-Chief, martyr of Syria”. The National identified the man on the poster as commander Reza Mousavi, a senior member of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps who ran operations in Syria until his assassination by Israel in December last year.

An orthopaedic surgeon, Dr Naim Trabzone, said that on one occasion, he was called in to treat a detainee with a tibia fracture that had gone untreated for days. It had become infected, suggesting the detainee was held in difficult confinement.

The patient was hooded and his hands were bound by handcuffs. Another detainee accompanied him, although Dr Trabzone said he didn’t treat the second patient.

‘Detainee Number One’ and ‘Detainee Number Two’ were written on the medical files Dr Trabzone was given on which to write his consultation.

He was told to treat Detainee One, “but they wouldn’t let me interact with him”. When the doctor prescribed painkillers and antibiotics, he said he was told in the Syrian dialect by his guards that Detainee One “won’t be getting any painkillers”.

The doctor said it was a common sight to see handcuffed detainees brought in for treatment at the hospital itself, but this was the only time – out of the dozens of times he was called in to treat patients throughout a two-year stint in 2022 and 2023 – that he saw detainees in the Friends Ward. He suspects they were brought in because they were high-profile prisoners of the regime’s State Security branch.

The National could not independently verify whether high-profile prisoners were treated at the Friends Ward.

Priority care

The National found two military uniforms – visually distinct from those of the Syrian army – strewn inside the Friends Ward.

Doctors said the foreign fighters were given priority treatment for what mainly were gunshot wounds and explosion-related injuries. Mr Ahmad called it an “express lane”.

The medical supply cabinet was well stocked despite the shortages of anaesthetic and other supplies in the rest of the hospital.

“If we were called up to treat someone up at [the] Friends [Ward], we had to go immediately,” Dr Jneidi, the thoracic surgeon, corroborated. “If they needed something like a CT scan it would happen within minutes.” But outside of the Friends Ward, for a normal patient of the hospital, “it might take hours for them to get a scan”.

“We would operate on them, and shortly after, they would get sent off to a different facility for the recovery process.”

The resentment of hospital staff was apparent, as they gave The National a tour of the ward.

“Sometimes, we would struggle to give adequate treatment to sick and injured people in the hospital. Meanwhile, these foreign fighters got the best care, medicine and food,” Dr Trabzone commented bitterly.

Dr Jneidi said his final stint in the Friends Ward was last Friday. On Saturday night, as rebel fighters swept victoriously into the Syrian capital, the ward was evacuated hurriedly.

In one of the treatment rooms, a tray of half-eaten food lay abandoned on a hospital bed.