When two newlywed British doctors started their careers in Africa, little did they realise their work to find out what was killing hundreds of young children would lead to millions of lives being saved.

Prof Sir Brian Greenwood and his wife Alice, a paediatrician, witnessed a large number of infant deaths and this set him on a path towards the creation of the world’s first malaria vaccine, and the first approved vaccine against a human parasitic disease.

After four decades of work dedicated to the fight against malaria, last year the world’s first vaccine against the disease was developed and given to millions of children.

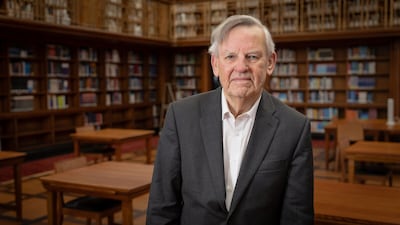

Sir Brian, who is now 85 and a research and teaching professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, found that the main reason children in Africa were dying was the mosquito-borne disease.

His interest in malaria was first sparked when he went to Nigeria in 1965 after graduating in medicine in the UK, and worked as a registrar at University College Hospital, Ibadan.

We have waited over three decades for a vaccine to be approved and now we have two in the space of a few years

Sir Brian Greenwood

While carrying out research for his thesis he discovered that there were very low incidences of autoimmune diseases among Nigerians, and he wondered if this could be linked to their repeated exposure to malaria.

He returned to the UK to continue training in immunology and was given the chance to help start a new medical school at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, in northern Nigeria, in 1970.

'Our initial lab was in the kitchen'

Not long afterwards the couple witnessed something they had not encountered before as hundreds of people were affected over a short period of time.

“One day we had one or two cases, the next day five cases of meningococcal, going up to 50 cases a day in a small hospital. We did a census to see what was actually killing the children,” he said. “At that time the mortality was about 300 in every 1,000, three in 10 children were dying.

“We had to find out what was going on and because there was no death certification, we thought of using postmortem questionnaires [with relatives of the dead].

“It was quite emotional. They were telling you what had happened, what the symptoms were, so we were able to build up a picture.

“There were two things they were dying of: pneumonia from chest infections and malaria.”

It was there that he set up the lab, initially in a kitchen, to begin researching malaria.

“It was tough as the [civil] war was just over, it was completely different from the big teaching hospitals,” Sir Brian said.

“We didn’t have many resources. Our initial lab was in the kitchen but we did get an immunology lab eventually.

“We were seeing what the immune system would do and we showed that actually if you had malaria your vaccines don’t work so well, because malaria was suppressing the immune response.

“My wife began administering drugs to young children to help prevent malaria, to see if it would make a difference.”

Two key breakthroughs

After 15 years the couple moved to Gambia, where he took up the post of director of the UK Medical Research Council Laboratories.

There he established a research programme focused on some of the most important infectious diseases prevalent in the region at that time, including malaria.

It was here that Sir Brian, who was knighted for his work in 2012, made two major breakthroughs in malaria protection.

He and his colleagues demonstrated the effectiveness of insecticide-treated nets in reducing child deaths and showed how net distribution could be incorporated successfully into a national malaria control programme.

“I set up two new field stations in the rural areas where we could start looking at malaria,” he said.

“I suddenly noticed that everybody in this rural village seemed to have a mosquito net, and that was not the case in the villages in Nigeria.

“We thought, 'Do people use the net to stop getting bitten, would it stop you getting malaria?'

“It was not a new idea as it had been used in colonial times, but then we looked at the literature to see if anybody had ever actually proven that that was the case, that having a bed net does protect you from malaria.

“And it does, so we started doing a study to show it did.

“Then people found a way to incorporate the insecticides into the nets and it was eventually picked up by the World Health Organisation.”

Malaria vaccine – in pictures

Another breakthrough followed when his team were able to show that mortality rates in young children from malaria could be reduced by giving them preventive drugs just a few months before the mosquito season.

“We had the idea that if expat children are protected then why don’t we do that for African children as well,” Sir Brian said.

“It seemed crazy if they were dying from malaria why we were not doing that.

“There was a lot of resistance in the 1980s because people were worried about resistance coming and they thought malaria prevention should only be for tourists and expats.

“My wife had been using drugs to help children not get malaria because she knew my children never had malaria, because they took their tablets.

“We started doing studies with malaria prevention in young children following on from what we had done in Nigeria and we showed that it really did work.”

Vaccine successes

Their work has paved the way for the preventions we see today.

In 1996, Sir Brian returned to the UK to take up an appointment at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where he continued his research on meningitis, malaria and pneumonia in West Africa.

He continued to build on the study in Gambia and conducted more trials, giving seasonal malaria prevention in Burkina Faso, Mali and Senegal.

It was a success and the results supported the earlier study’s findings.

This led to a recommendation from the WHO for preventive medicines in countries of the Sahel and sub-Sahel, with more than 30 million children now receiving the drugs each year.

Sir Brian then worked on the design of the first GSK malaria vaccine RTS, S, which in 2021 became the world's first malaria vaccine and the first approved vaccine to battle a human parasitic disease.

The first trials' success led to a pilot programme and now it has finally been recommended by the WHO to be used as a seasonal vaccine in countries of sub-Saharan Africa with a high malaria risk.

More than two million children have been given the vaccine and deaths in the affected areas have so far been cut by 13 per cent.

His work has shown that when a seasonal vaccination was combined with chemoprevention drugs it provided a very high level of protection to children over the first five years of their lives.

The results from this study have also helped the development of the second malaria vaccine, called R21, which was introduced last year and has many similar properties to RTS, S.

Despite the breakthroughs, Sir Brian’s biggest regret is that it took too long.

In 2022 the disease caused more than 600,000 deaths, nearly all in young African children, but the new vaccines that are now rolling off the production lines can finally spare millions of lives.

“There are lessons to be learnt,” Sir Brian said. “Ten years ago when Ebola broke out in Sierra Leone I was asked to help out with a vaccine and we did that in five years.

“Malaria is much more complicated but it should not have taken 30 years.

“Looking at where the gaps were and how it could be speeded up helped create the second vaccine, R21, and it benefitted from the experience in developing the first one.

“We have waited over three decades for a vaccine to be approved and now we have two in the space of a few years.

“But it is not a silver bullet. More research is needed to create a vaccine that can offer longer protection. That is the next step now.”

'It was a team effort'

Despite his work in helping to develop the vaccines, Sir Brian's greatest achievement remains training the next generation of scientists in Africa to continue the fight against malaria.

In 2001, he received a large grant to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to set up the Gates Malaria Partnership, which supported the training in research of 40 African PhD students and postdoctoral fellows.

Sir Brian became the director of its successor programme, the Malaria Capacity Development Consortium, in 2008.

It was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which supported a postgraduate malaria training programme in five universities in sub-Saharan Africa.

“We have to keep up the funding. For the last eight years I have been chair of a WHO elimination commission to certify countries which have eliminated malaria and I send out teams to see if it is really true.

“Since we set this up, about 15 countries have been certified as having eliminated it.

“This year Cape Verde and Georgia are on the list. Gradually the map is shrinking but more needs to be done.”

After his achievements in the battle against malaria, Sir Brian was awarded his knighthood in the UK's honours list.

“It was a team effort,” he said. “I could have ended up in Harley Street and had a big house in the south of France but I have absolutely no regrets.”

From Zero

Artist: Linkin Park

Label: Warner Records

Number of tracks: 11

Rating: 4/5

MOUNTAINHEAD REVIEW

Starring: Ramy Youssef, Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman

Director: Jesse Armstrong

Rating: 3.5/5

Company profile

Name: GiftBag.ae

Based: Dubai

Founded: 2011

Number of employees: 4

Sector: E-commerce

Funding: Self-funded to date

Tightening the screw on rogue recruiters

The UAE overhauled the procedure to recruit housemaids and domestic workers with a law in 2017 to protect low-income labour from being exploited.

Only recruitment companies authorised by the government are permitted as part of Tadbeer, a network of labour ministry-regulated centres.

A contract must be drawn up for domestic workers, the wages and job offer clearly stating the nature of work.

The contract stating the wages, work entailed and accommodation must be sent to the employee in their home country before they depart for the UAE.

The contract will be signed by the employer and employee when the domestic worker arrives in the UAE.

Only recruitment agencies registered with the ministry can undertake recruitment and employment applications for domestic workers.

Penalties for illegal recruitment in the UAE include fines of up to Dh100,000 and imprisonment

But agents not authorised by the government sidestep the law by illegally getting women into the country on visit visas.

How has net migration to UK changed?

The figure was broadly flat immediately before the Covid-19 pandemic, standing at 216,000 in the year to June 2018 and 224,000 in the year to June 2019.

It then dropped to an estimated 111,000 in the year to June 2020 when restrictions introduced during the pandemic limited travel and movement.

The total rose to 254,000 in the year to June 2021, followed by steep jumps to 634,000 in the year to June 2022 and 906,000 in the year to June 2023.

The latest available figure of 728,000 for the 12 months to June 2024 suggests levels are starting to decrease.

EA Sports FC 26

Publisher: EA Sports

Consoles: PC, PlayStation 4/5, Xbox Series X/S

Rating: 3/5

DEADPOOL & WOLVERINE

Starring: Ryan Reynolds, Hugh Jackman, Emma Corrin

Director: Shawn Levy

Rating: 3/5

The candidates

Dr Ayham Ammora, scientist and business executive

Ali Azeem, business leader

Tony Booth, professor of education

Lord Browne, former BP chief executive

Dr Mohamed El-Erian, economist

Professor Wyn Evans, astrophysicist

Dr Mark Mann, scientist

Gina MIller, anti-Brexit campaigner

Lord Smith, former Cabinet minister

Sandi Toksvig, broadcaster

Ferrari 12Cilindri specs

Engine: naturally aspirated 6.5-liter V12

Power: 819hp

Torque: 678Nm at 7,250rpm

Price: From Dh1,700,000

Available: Now

FA%20Cup%20semi-final%20draw

%3Cp%3ECoventry%20City%20v%20Manchester%20United%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EManchester%20City%20v%20Chelsea%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20Games%20to%20be%20played%20at%20Wembley%20Stadium%20on%20weekend%20of%20April%2020%2F21.%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere

Director: Scott Cooper

Starring: Jeremy Allen White, Odessa Young, Jeremy Strong

Rating: 4/5

Where to donate in the UAE

The Emirates Charity Portal

You can donate to several registered charities through a “donation catalogue”. The use of the donation is quite specific, such as buying a fan for a poor family in Niger for Dh130.

The General Authority of Islamic Affairs & Endowments

The site has an e-donation service accepting debit card, credit card or e-Dirham, an electronic payment tool developed by the Ministry of Finance and First Abu Dhabi Bank.

Al Noor Special Needs Centre

You can donate online or order Smiles n’ Stuff products handcrafted by Al Noor students. The centre publishes a wish list of extras needed, starting at Dh500.

Beit Al Khair Society

Beit Al Khair Society has the motto “From – and to – the UAE,” with donations going towards the neediest in the country. Its website has a list of physical donation sites, but people can also contribute money by SMS, bank transfer and through the hotline 800-22554.

Dar Al Ber Society

Dar Al Ber Society, which has charity projects in 39 countries, accept cash payments, money transfers or SMS donations. Its donation hotline is 800-79.

Dubai Cares

Dubai Cares provides several options for individuals and companies to donate, including online, through banks, at retail outlets, via phone and by purchasing Dubai Cares branded merchandise. It is currently running a campaign called Bookings 2030, which allows people to help change the future of six underprivileged children and young people.

Emirates Airline Foundation

Those who travel on Emirates have undoubtedly seen the little donation envelopes in the seat pockets. But the foundation also accepts donations online and in the form of Skywards Miles. Donated miles are used to sponsor travel for doctors, surgeons, engineers and other professionals volunteering on humanitarian missions around the world.

Emirates Red Crescent

On the Emirates Red Crescent website you can choose between 35 different purposes for your donation, such as providing food for fasters, supporting debtors and contributing to a refugee women fund. It also has a list of bank accounts for each donation type.

Gulf for Good

Gulf for Good raises funds for partner charity projects through challenges, like climbing Kilimanjaro and cycling through Thailand. This year’s projects are in partnership with Street Child Nepal, Larchfield Kids, the Foundation for African Empowerment and SOS Children's Villages. Since 2001, the organisation has raised more than $3.5 million (Dh12.8m) in support of over 50 children’s charities.

Noor Dubai Foundation

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum launched the Noor Dubai Foundation a decade ago with the aim of eliminating all forms of preventable blindness globally. You can donate Dh50 to support mobile eye camps by texting the word “Noor” to 4565 (Etisalat) or 4849 (du).

Key facilities

- Olympic-size swimming pool with a split bulkhead for multi-use configurations, including water polo and 50m/25m training lanes

- Premier League-standard football pitch

- 400m Olympic running track

- NBA-spec basketball court with auditorium

- 600-seat auditorium

- Spaces for historical and cultural exploration

- An elevated football field that doubles as a helipad

- Specialist robotics and science laboratories

- AR and VR-enabled learning centres

- Disruption Lab and Research Centre for developing entrepreneurial skills

The%20specs

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202-litre%204-cylinder%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E153hp%20at%206%2C000rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E200Nm%20at%204%2C000rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E6-speed%20auto%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFuel%20consumption%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E6.3L%2F100km%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDh106%2C900%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Enow%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESmartCrowd%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2018%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounder%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESiddiq%20Farid%20and%20Musfique%20Ahmed%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDubai%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFinTech%20%2F%20PropTech%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInitial%20investment%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%24650%2C000%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECurrent%20number%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2035%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeries%20A%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EVarious%20institutional%20investors%20and%20notable%20angel%20investors%20(500%20MENA%2C%20Shurooq%2C%20Mada%2C%20Seedstar%2C%20Tricap)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The five pillars of Islam

1. Fasting

2. Prayer

3. Hajj

4. Shahada

5. Zakat

The specs: 2018 Nissan 370Z Nismo

The specs: 2018 Nissan 370Z Nismo

Price, base / as tested: Dh182,178

Engine: 3.7-litre V6

Power: 350hp @ 7,400rpm

Torque: 374Nm @ 5,200rpm

Transmission: Seven-speed automatic

Fuel consumption, combined: 10.5L / 100km

Skoda Superb Specs

Engine: 2-litre TSI petrol

Power: 190hp

Torque: 320Nm

Price: From Dh147,000

Available: Now

Director: Laxman Utekar

Cast: Vicky Kaushal, Akshaye Khanna, Diana Penty, Vineet Kumar Singh, Rashmika Mandanna

Rating: 1/5

If you go...

Etihad flies daily from Abu Dhabi to Zurich, with fares starting from Dh2,807 return. Frequent high speed trains between Zurich and Vienna make stops at St. Anton.

Tenet

Director: Christopher Nolan

Stars: John David Washington, Robert Pattinson, Elizabeth Debicki, Dimple Kapadia, Michael Caine, Kenneth Branagh

Rating: 5/5

SPEC%20SHEET%3A%20NOTHING%20PHONE%20(2)

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%206.7%E2%80%9D%20LPTO%20Amoled%2C%202412%20x%201080%2C%20394ppi%2C%20HDR10%2B%2C%20Corning%20Gorilla%20Glass%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Qualcomm%20Snapdragon%208%2B%20Gen%202%2C%20octa-core%3B%20Adreno%20730%20GPU%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%208%2F12GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECapacity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20128%2F256%2F512GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPlatform%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Android%2013%2C%20Nothing%20OS%202%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMain%20camera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dual%2050MP%20wide%2C%20f%2F1.9%20%2B%2050MP%20ultrawide%2C%20f%2F2.2%3B%20OIS%2C%20auto-focus%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMain%20camera%20video%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204K%20%40%2030%2F60fps%2C%201080p%20%40%2030%2F60fps%3B%20live%20HDR%2C%20OIS%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFront%20camera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2032MP%20wide%2C%20f%2F2.5%2C%20HDR%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFront%20camera%20video%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Full-HD%20%40%2030fps%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204700mAh%3B%20full%20charge%20in%2055m%20w%2F%2045w%20charger%3B%20Qi%20wireless%2C%20dual%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Wi-Fi%2C%20Bluetooth%205.3%2C%20NFC%20(Google%20Pay)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBiometrics%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Fingerprint%2C%20face%20unlock%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EI%2FO%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20USB-C%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDurability%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20IP54%2C%20limited%20protection%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECards%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dual-nano%20SIM%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EColours%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dark%20grey%2C%20white%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Nothing%20Phone%20(2)%2C%20USB-C-to-USB-C%20cable%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%20(UAE)%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dh2%2C499%20(12GB%2F256GB)%20%2F%20Dh2%2C799%20(12GB%2F512GB)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Specs

Engine: Electric motor generating 54.2kWh (Cooper SE and Aceman SE), 64.6kW (Countryman All4 SE)

Power: 218hp (Cooper and Aceman), 313hp (Countryman)

Torque: 330Nm (Cooper and Aceman), 494Nm (Countryman)

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh158,000 (Cooper), Dh168,000 (Aceman), Dh190,000 (Countryman)

The Sand Castle

Director: Matty Brown

Stars: Nadine Labaki, Ziad Bakri, Zain Al Rafeea, Riman Al Rafeea

Rating: 2.5/5

Related

BMW M5 specs

Engine: 4.4-litre twin-turbo V-8 petrol enging with additional electric motor

Power: 727hp

Torque: 1,000Nm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 10.6L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh650,000

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Clinicy%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202017%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Prince%20Mohammed%20Bin%20Abdulrahman%2C%20Abdullah%20bin%20Sulaiman%20Alobaid%20and%20Saud%20bin%20Sulaiman%20Alobaid%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Riyadh%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2025%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20HealthTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETotal%20funding%20raised%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20More%20than%20%2410%20million%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Middle%20East%20Venture%20Partners%2C%20Gate%20Capital%2C%20Kafou%20Group%20and%20Fadeed%20Investment%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Studying addiction

This month, Dubai Medical College launched the Middle East’s first master's programme in addiction science.

Together with the Erada Centre for Treatment and Rehabilitation, the college offers a two-year master’s course as well as a one-year diploma in the same subject.

The move was announced earlier this year and is part of a new drive to combat drug abuse and increase the region’s capacity for treating drug addiction.

School counsellors on mental well-being

Schools counsellors in Abu Dhabi have put a number of provisions in place to help support pupils returning to the classroom next week.

Many children will resume in-person lessons for the first time in 10 months and parents previously raised concerns about the long-term effects of distance learning.

Schools leaders and counsellors said extra support will be offered to anyone that needs it. Additionally, heads of years will be on hand to offer advice or coping mechanisms to ease any concerns.

“Anxiety this time round has really spiralled, more so than from the first lockdown at the beginning of the pandemic,” said Priya Mitchell, counsellor at The British School Al Khubairat in Abu Dhabi.

“Some have got used to being at home don’t want to go back, while others are desperate to get back.

“We have seen an increase in depressive symptoms, especially with older pupils, and self-harm is starting younger.

“It is worrying and has taught us how important it is that we prioritise mental well-being.”

Ms Mitchell said she was liaising more with heads of year so they can support and offer advice to pupils if the demand is there.

The school will also carry out mental well-being checks so they can pick up on any behavioural patterns and put interventions in place to help pupils.

At Raha International School, the well-being team has provided parents with assessment surveys to see how they can support students at home to transition back to school.

“They have created a Well-being Resource Bank that parents have access to on information on various domains of mental health for students and families,” a team member said.

“Our pastoral team have been working with students to help ease the transition and reduce anxiety that [pupils] may experience after some have been nearly a year off campus.

"Special secondary tutorial classes have also focused on preparing students for their return; going over new guidelines, expectations and daily schedules.”