What were famed Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta’s first impressions of Sharjah more than 700 years ago? And how did Emirati navigator Ahmad Ibn Majid shape the course of maritime history?

These were among the topics explored during discussions at the Sharjah pavilion at the Rabat International Book Fair. Held in the heart of the Moroccan capital and running until April 27, the fair is in its 30th year, with Sharjah participating as guest of honour.

As part of its designation, the emirate presented a packed opening weekend programme featuring more than a dozen authors, poets and historians, highlighting the deep-rooted cultural ties between the UAE and the North African kingdom.

“It is an important relationship that still endures today, often in ways we don’t realise or tend to take for granted,” said Abdulaziz Al Musallam, chairman of the Sharjah Institute for Heritage. Speaking to The National at the book fair, he pointed to the shared linguistic roots found in everyday Arabic words across the Gulf and Morocco. “Even our Emirati dialect reflect the connection. We say ‘zein’ [good], they say ‘zwina.’ We say gahwa [coffee], they say ‘qhwa’ or ‘qahiwa’ – it’s the same word, just with different variations.”

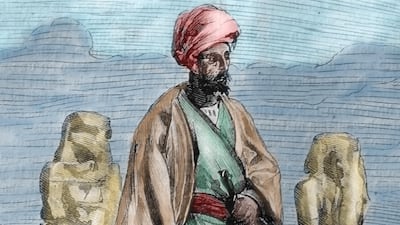

A celebrated tie between the UAE and Oman, Al Musallam says, is the 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta, who sailed along the Arabian Gulf coast and is believed to have passed through Sharjah towns such as Kalba, Khor Fakkan, and Dibba – then largely under the control of Kingdom of Hormuz.

"It seems Ibn Battuta arrived during the winter, because he said Kalba had rivers and green meadows. He saw green trees and a flowing valley – it was vast and it's a place with a lot of water. Then he moved on and described Khor Fakkan too," Al Musallam says. "Then, it seems it became summer, so he went to Dibba and said that at night something came down from the sky like molasses – you know, the black syrup. What he saw was humidity. Then he entered the Gulf but didn’t refer to it as the Gulf; he called it the Sea of Siraf. That’s mentioned in some old manuscripts."

Many of these experiences are recorded in The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325–1354, a multi-volume work that has been translated from the original Arabic text and published in various editions over the years. Revered as a cornerstone of travel literature, Ibn Battuta’s writings owe their conversational tone and spontaneity to the fact that they were recounted from memory rather than compiled from extensive notes, Al Musallam says. The result is often a rollicking – and at times unfiltered – account of his escapades.

“He was essentially an oral storyteller. From my own experience working with such narrators over the past 30 years, you realise one storyteller can tell the same story in four different ways over four sittings – adding a little here, omitting there. It depends on the audience in that if they like a topic, the storyteller would emphasise it. If not, he downplays or hides it,” he says.

“Ibn Battuta’s travelogue represents the Arab model of the wandering narrator – someone unfiltered, sometimes painfully honest. Some people may now find this style inappropriate, but that was normal in Arab storytelling – to say things bluntly, both the good and the bad.”

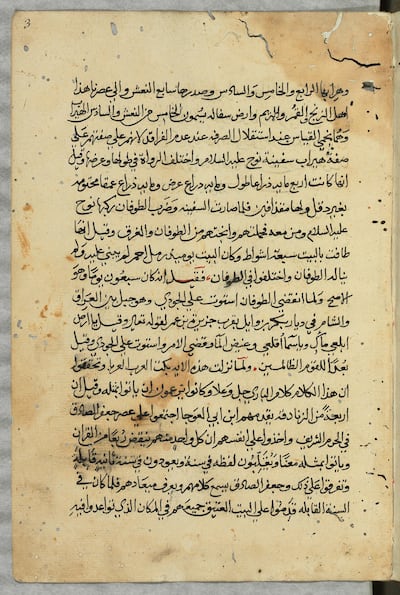

As for Ahmad Ibn Majid, the 15th-century navigator born in Julfar, present-day Ras Al Khaimah, he preferred to share his maritime knowledge through poetry. Many of his verses were compiled in volumes including the seminal Kitab al-Fawa’id fi Usul ‘Ilm al-Bahr wa’l Qawa’id (The Book of Useful Information on the Principles and Rules of Navigation) – a work widely regarded as a foundational text of classical Arab navigation.

In a Saturday session exploring his influence, UAE poet and researcher Shaikha Al Mutairi states that Ahmad Ibn Majid is also credited as one of the first Arab navigators to describe the use of the compass – thought to have been invented in China as early as the 2nd century BCE and adopted for navigation by the 11th century.

“He described it as a deep cup, and at the bottom of the cup is black paper which influences the direction of the indicator,” Al Mutairi says. “His father was a great sailor, so Ahmad Ibn Majid inherited this legacy. While we don’t have many records of his father, Ahmad’s impact spread across the Gulf – not just in the UAE or Oman. Kuwaiti sailors relied heavily on his poetic navigational rhymes. So did sailors in Basra and East Africa.”

Another key reason for that wide reach, Al Mutairi notes, is how Ibn Majid transmitted dry and practical information through rajaz verses – a classical form of Arabic poetry often used for improvisation due to its short, repetitive and rhythmic style. “He uses beautiful literary expressions, powerful introductions and emotive language,” she says.

“There’s also a deeper psychological layer in his poetry. Sometimes it feels as if he’s defending himself when he says, ‘I’m fine. I’m skilled. I’m knowledgeable.’ It makes you think – what was he going through at the time? We don’t know, but he often states his name and lineage again and again – as a way of affirming his identity.”

COMPANY PROFILE

Initial investment: Undisclosed

Investment stage: Series A

Investors: Core42

Current number of staff: 47

Kill%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Nikhil%20Nagesh%20Bhat%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20Lakshya%2C%20Tanya%20Maniktala%2C%20Ashish%20Vidyarthi%2C%20Harsh%20Chhaya%2C%20Raghav%20Juyal%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204.5%2F5%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

In numbers: China in Dubai

The number of Chinese people living in Dubai: An estimated 200,000

Number of Chinese people in International City: Almost 50,000

Daily visitors to Dragon Mart in 2018/19: 120,000

Daily visitors to Dragon Mart in 2010: 20,000

Percentage increase in visitors in eight years: 500 per cent

Lexus LX700h specs

Engine: 3.4-litre twin-turbo V6 plus supplementary electric motor

Power: 464hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 790Nm from 2,000-3,600rpm

Transmission: 10-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 11.7L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh590,000

WHAT IS A BLACK HOLE?

1. Black holes are objects whose gravity is so strong not even light can escape their pull

2. They can be created when massive stars collapse under their own weight

3. Large black holes can also be formed when smaller ones collide and merge

4. The biggest black holes lurk at the centre of many galaxies, including our own

5. Astronomers believe that when the universe was very young, black holes affected how galaxies formed

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Dhadak 2

Director: Shazia Iqbal

Starring: Siddhant Chaturvedi, Triptii Dimri

Rating: 1/5

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere

Director: Scott Cooper

Starring: Jeremy Allen White, Odessa Young, Jeremy Strong

Rating: 4/5

SPEC%20SHEET%3A%20APPLE%20M3%20MACBOOK%20AIR%20(13%22)

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Apple%20M3%2C%208-core%20CPU%2C%20up%20to%2010-core%20CPU%2C%2016-core%20Neural%20Engine%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2013.6-inch%20Liquid%20Retina%2C%202560%20x%201664%2C%20224ppi%2C%20500%20nits%2C%20True%20Tone%2C%20wide%20colour%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%208%2F16%2F24GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStorage%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20256%2F512GB%20%2F%201%2F2TB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EI%2FO%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Thunderbolt%203%2FUSB-4%20(2)%2C%203.5mm%20audio%2C%20Touch%20ID%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Wi-Fi%206E%2C%20Bluetooth%205.3%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2052.6Wh%20lithium-polymer%2C%20up%20to%2018%20hours%2C%20MagSafe%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECamera%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201080p%20FaceTime%20HD%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EVideo%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Support%20for%20Apple%20ProRes%2C%20HDR%20with%20Dolby%20Vision%2C%20HDR10%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EAudio%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204-speaker%20system%2C%20wide%20stereo%2C%20support%20for%20Dolby%20Atmos%2C%20Spatial%20Audio%20and%20dynamic%20head%20tracking%20(with%20AirPods)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EColours%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Midnight%2C%20silver%2C%20space%20grey%2C%20starlight%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20MacBook%20Air%2C%2030W%2F35W%20dual-port%2F70w%20power%20adapter%2C%20USB-C-to-MagSafe%20cable%2C%202%20Apple%20stickers%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20From%20Dh4%2C599%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

GAC GS8 Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 248hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 400Nm at 1,750-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 9.1L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh149,900

TOURNAMENT INFO

Women’s World Twenty20 Qualifier

Jul 3- 14, in the Netherlands

The top two teams will qualify to play at the World T20 in the West Indies in November

UAE squad

Humaira Tasneem (captain), Chamani Seneviratne, Subha Srinivasan, Neha Sharma, Kavisha Kumari, Judit Cleetus, Chaya Mughal, Roopa Nagraj, Heena Hotchandani, Namita D’Souza, Ishani Senevirathne, Esha Oza, Nisha Ali, Udeni Kuruppuarachchi

The years Ramadan fell in May

Score

New Zealand 266 for 9 in 50 overs

Pakistan 219 all out in 47.2 overs

New Zealand win by 47 runs

New Zealand lead three-match ODI series 1-0

Next match: Zayed Cricket Stadium, Abu Dhabi, Friday

Tamkeen's offering

- Option 1: 70% in year 1, 50% in year 2, 30% in year 3

- Option 2: 50% across three years

- Option 3: 30% across five years

Scores

Wales 74-24 Tonga

England 35-15 Japan

Italy 7-26 Australia

Ferrari 12Cilindri specs

Engine: naturally aspirated 6.5-liter V12

Power: 819hp

Torque: 678Nm at 7,250rpm

Price: From Dh1,700,000

Available: Now

The specs: Macan Turbo

Engine: Dual synchronous electric motors

Power: 639hp

Torque: 1,130Nm

Transmission: Single-speed automatic

Touring range: 591km

Price: From Dh412,500

On sale: Deliveries start in October

Ruwais timeline

1971 Abu Dhabi National Oil Company established

1980 Ruwais Housing Complex built, located 10 kilometres away from industrial plants

1982 120,000 bpd capacity Ruwais refinery complex officially inaugurated by the founder of the UAE Sheikh Zayed

1984 Second phase of Ruwais Housing Complex built. Today the 7,000-unit complex houses some 24,000 people.

1985 The refinery is expanded with the commissioning of a 27,000 b/d hydro cracker complex

2009 Plans announced to build $1.2 billion fertilizer plant in Ruwais, producing urea

2010 Adnoc awards $10bn contracts for expansion of Ruwais refinery, to double capacity from 415,000 bpd

2014 Ruwais 261-outlet shopping mall opens

2014 Production starts at newly expanded Ruwais refinery, providing jet fuel and diesel and allowing the UAE to be self-sufficient for petrol supplies

2014 Etihad Rail begins transportation of sulphur from Shah and Habshan to Ruwais for export

2017 Aldar Academies to operate Adnoc’s schools including in Ruwais from September. Eight schools operate in total within the housing complex.

2018 Adnoc announces plans to invest $3.1 billion on upgrading its Ruwais refinery

2018 NMC Healthcare selected to manage operations of Ruwais Hospital

2018 Adnoc announces new downstream strategy at event in Abu Dhabi on May 13

Source: The National

MATCH INFO

Inter Milan 2 (Vecino 65', Barella 83')

Verona 1 (Verre 19' pen)