Syria has been left broken and divided by the civil war that has raged since 2011, when security forces cracked down on peaceful protesters. President Bashar Al Assad's regime has survived, but at a bloody cost.

About 500,000 have been killed in the fighting that continues sporadically to this day, millions of Syrians have fled abroad, cities have been destroyed and sectarian divisions have become entrenched. While the ruined nation may appear beyond repair, a new book by a leading historian of the Arab world offers a model of hope from Syria's own history for how the long process of reconstruction and reconciliation might begin.

Professor Eugene Rogan’s The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Destruction of the Old Ottoman World explores the causes and consequences of the massacre of thousands of Christians by their Muslim neighbours in Damascus in the mid-19th century.

Drawing on an array of historical sources and a cast of colourful characters from the period, Rogan recounts how the people of Damascus descended from living in relative harmony into a “genocidal moment”.

While the ominously named Hawadith ash-Sham, or the Damascus Events, may reveal the darker side of human nature, Rogan suggests Ottoman authorities were largely successful in pulling the city back from the brink and fostering long-term reconciliation.

“I hope that for Syrians to see that in the mid-19th century, there were local solutions to local problems, that there is a pathway back from the brink of mass murder towards reconstruction, and, with reconstruction, through providing the prospect of a better future for the next generation, you can achieve reconciliation,” he tells The National.

Rogan locates the long-term context of the massacres in the history of Damascus, a city he visited often from a childhood home in Beirut, and whose archives he consulted in his research.

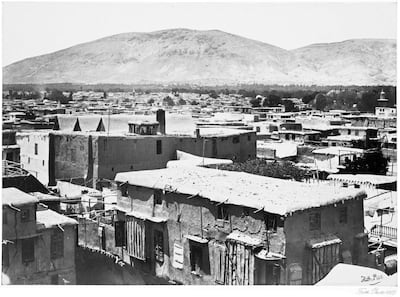

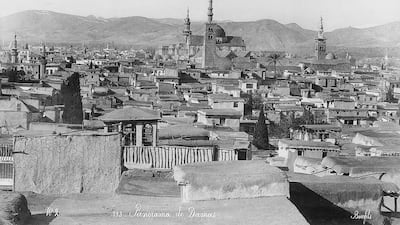

In the early 19th century, Damascus was one of the major provincial capitals of the Ottoman Empire. Damascenes were known for taking pride in their city, which was nicknamed Damascus the Fragrant, and considered one of the hearts of the Islamic world.

Hub city

While Damascus was an important Islamic centre, in part due to its historic role as a departure point for the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Makkah, the city was home to a diverse population. By the mid-19th century, about 85 per cent of the city's inhabitants were Muslims, including Arabs, Turks, Kurds and Persians. About 10 to 12 per cent were Christians from various sects, with a small Jewish population of less than 5 per cent.

Under Ottoman law, Christians and Jews were granted security and property, but were legally second-class citizens. Despite the rigid religious and social hierarchy, intercommunal outbursts of violence were rare. This order began to unravel through the first half of the 19th century as social and economic change swept Syria, stoking tensions between the Muslim majority population and minorities.

Beginning in the 1830s, European influence on the Ottoman Empire increased, and the region began to undergo rapid societal upheaval. Damascus had already been losing economic importance as the Ottoman Empire entered European markets, with trade shifting to the coastal city of Beirut.

While many Muslims fell on hard times, Christians began to benefit from the influx of European goods and trade. Employment as economic agents and consular staff granted them economic privileges over their Muslim competitors.

In 1856, under pressure from European powers, the Ottoman government granted Christians and Jews legal equality for the first time. These changes laid the ground for growing resentment among Muslims, who saw Christians as upending the social order and arrogantly flaunting their newfound privileges.

"Violence was brewing. There was a growing perception that the Christians of Damascus were in some ways displacing the role of the Muslim elite as the dominant group in the city," Rogan says.

In early 1860, the Druze massacres of Maronite Christian civilians in neighbouring Lebanon provided a "precedent" for Muslims in Damascus. Having identified the local Christian community as an existential threat to their standing, wealth and position, “they began to conceive of extermination as a reasonable solution".

During eight days of unprecedented lawlessness, a mostly Muslim crowd attempted to exterminate the Christian population. An estimated 5,000 were killed. Hundreds more were forcibly converted, with children abducted to be brought up as Muslims, and women were raped. The churches of Damascus were destroyed and the homes of most Christians were burned down.

Eighty-five per cent of the population, however, was saved, primarily by the Algerian anti-colonial leader Abd al-Qadir and his men stationed in the city, along with some of the Muslim elite, who provided shelter.

In the aftermath of the massacres, the city was left deeply divided with Christians fearing further attacks, and Muslims fearing revenge. The Ottoman authorities needed not only to restore law and order but also to heal these tensions and restore peace and prosperity. The situation was further complicated by pressure from European powers, whose demands for revenge for their Christian proteges were backed by the potential threat of a military occupation of Syria.

Rogan argues that the Ottomans dealt with these challenges slowly but admirably and ultimately effectively. He charts how thousands of Muslims who were implicated in the riots were arrested shortly after the arrival in the city of the newly appointed Ottoman governor, Fuad Pasha. More than 150 were executed, including the former governor, who had failed to stop the massacres.

While control was regained, many Muslims resented the draconian punishments and Damascus remained divided.

Tax to rebuild

The badly damaged city needed restoration, while most of the Christian population had lost everything they owned and needed compensation. Partly to placate European demands, the Ottomans imposed a tax on Muslims to pay for the losses. Although the money raised was insufficient, it allowed Christians to begin to rebuild their homes.

The true process of reconciliation came with the onset of economic opportunities and shared prosperity from the mid-1860s onwards. Central to the Ottoman plan was the creation of a new province, or vilayet, of Syria in 1865, combining the provinces of Damascus, Jerusalem and Sidon. Damascus was made the capital of the new province, and the combined tax revenues were funnelled into the city.

"It created five times the revenues flowing through Damascus, allowing massive infrastructural investment, creating markets and jobs, communications, infrastructure, education opportunities," explains Rogan.

Crucially, the newfound prosperity was shared between different communities. An elected general council comprised of Muslims and Christians from across Syria was tasked with ensuring spending was shared equitably.

"Suddenly, the gains of one side are not at the expense of the other," he says. In this process, Rogan sees potential inspiration for today’s Syria.

While Syrians still criticised elements of Ottoman rule, including corruption, shared prosperity allowed the city’s divided groups to live and work together again. Unlike in neighbouring Lebanon, where 1860 is seen as the origin of a sectarian system that still endures today, Rogan says that Syria did not inherit a sectarian legacy.

Instead, most Syrians embraced a shared secular national identity, from Ottoman rule through the French mandate period and into independence. While there have been outbreaks of communal violence in Syria, it was not until 2011 that the country descended into mass sectarian division and bloodshed.

Rogan points out that both the context and the magnitude of today’s crisis make it in some ways “incomparable” to 1860. Whereas the Ottoman authorities were able to restore order and pump funds into Damascus, today the Syrian government controls only 70 per cent of the country and depends on its Russian and Iranian backers.

About 90 per cent of Syrians are currently living below the poverty line and reconstruction estimates range from $250 billion up to $1 trillion.

Next generation

Even then, Syria is only one of many “broken countries” in the region requiring reconstruction, including Iraq, Libya, Yemen and most recently Gaza, spreading international funding and attention thin. The regime has also lost the trust of many of its people and has alienated much of the diaspora living in exile.

For these reasons, Rogan says it is hard to conceive of reconstruction happening under the Assad regime. Yet he believes that history still provides an encouraging message for the region today in spite of the fragmentation of the past 13 years.

"It is the prospect of a better future for the next generation that will enable the current generation to lay down the hatchet and turn the page to move forward," he says. “There is hope that Syria will one day, once again, restore its sense of community and civility, to be a whole country."

The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Destruction of the Old Ottoman World by Eugene Rogan is available in hardback now.

THE BIO

Favourite book: ‘Purpose Driven Life’ by Rick Warren

Favourite travel destination: Switzerland

Hobbies: Travelling and following motivational speeches and speakers

Favourite place in UAE: Dubai Museum

Quick facts on cancer

- Cancer is the second-leading cause of death worldwide, after cardiovascular diseases

- About one in five men and one in six women will develop cancer in their lifetime

- By 2040, global cancer cases are on track to reach 30 million

- 70 per cent of cancer deaths occur in low and middle-income countries

- This rate is expected to increase to 75 per cent by 2030

- At least one third of common cancers are preventable

- Genetic mutations play a role in 5 per cent to 10 per cent of cancers

- Up to 3.7 million lives could be saved annually by implementing the right health

strategies

- The total annual economic cost of cancer is $1.16 trillion

RACE CARD

6.30pm: Maiden (TB) Dh82,500 (Dirt) 1,200m

7.05pm: Maiden (TB) Dh82,500 (D) 1,900m

7.40pm: Handicap (TB) Dh102,500 (D) 2,000m

8.15pm: Conditions (TB) Dh120,000 (D) 1,600m

8.50pm: Handicap (TB) Dh95,000 (D) 1,600m

9.25pm: Handicap (TB) Dh87,500 (D) 1,400m

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Key facilities

- Olympic-size swimming pool with a split bulkhead for multi-use configurations, including water polo and 50m/25m training lanes

- Premier League-standard football pitch

- 400m Olympic running track

- NBA-spec basketball court with auditorium

- 600-seat auditorium

- Spaces for historical and cultural exploration

- An elevated football field that doubles as a helipad

- Specialist robotics and science laboratories

- AR and VR-enabled learning centres

- Disruption Lab and Research Centre for developing entrepreneurial skills

Miss Granny

Director: Joyce Bernal

Starring: Sarah Geronimo, James Reid, Xian Lim, Nova Villa

3/5

(Tagalog with Eng/Ar subtitles)

KEY%20DATES%20IN%20AMAZON'S%20HISTORY

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EJuly%205%2C%201994%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Jeff%20Bezos%20founds%20Cadabra%20Inc%2C%20which%20would%20later%20be%20renamed%20to%20Amazon.com%2C%20because%20his%20lawyer%20misheard%20the%20name%20as%20'cadaver'.%20In%20its%20earliest%20days%2C%20the%20bookstore%20operated%20out%20of%20a%20rented%20garage%20in%20Bellevue%2C%20Washington%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EJuly%2016%2C%201995%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20formally%20opens%20as%20an%20online%20bookseller.%20%3Cem%3EFluid%20Concepts%20and%20Creative%20Analogies%3A%20Computer%20Models%20of%20the%20Fundamental%20Mechanisms%20of%20Thought%3C%2Fem%3E%20becomes%20the%20first%20item%20sold%20on%20Amazon%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E1997%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20goes%20public%20at%20%2418%20a%20share%2C%20which%20has%20grown%20about%201%2C000%20per%20cent%20at%20present.%20Its%20highest%20closing%20price%20was%20%24197.85%20on%20June%2027%2C%202024%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E1998%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20acquires%20IMDb%2C%20its%20first%20major%20acquisition.%20It%20also%20starts%20selling%20CDs%20and%20DVDs%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2000%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20Marketplace%20opens%2C%20allowing%20people%20to%20sell%20items%20on%20the%20website%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2002%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20forms%20what%20would%20become%20Amazon%20Web%20Services%2C%20opening%20the%20Amazon.com%20platform%20to%20all%20developers.%20The%20cloud%20unit%20would%20follow%20in%202006%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2003%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20turns%20in%20an%20annual%20profit%20of%20%2475%20million%2C%20the%20first%20time%20it%20ended%20a%20year%20in%20the%20black%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2005%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20Prime%20is%20introduced%2C%20its%20first-ever%20subscription%20service%20that%20offered%20US%20customers%20free%20two-day%20shipping%20for%20%2479%20a%20year%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2006%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20Unbox%20is%20unveiled%2C%20the%20company's%20video%20service%20that%20would%20later%20morph%20into%20Amazon%20Instant%20Video%20and%2C%20ultimately%2C%20Amazon%20Video%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2007%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon's%20first%20hardware%20product%2C%20the%20Kindle%20e-reader%2C%20is%20introduced%3B%20the%20Fire%20TV%20and%20Fire%20Phone%20would%20come%20in%202014.%20Grocery%20service%20Amazon%20Fresh%20is%20also%20started%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2009%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20introduces%20Amazon%20Basics%2C%20its%20in-house%20label%20for%20a%20variety%20of%20products%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2010%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20The%20foundations%20for%20Amazon%20Studios%20were%20laid.%20Its%20first%20original%20streaming%20content%20debuted%20in%202013%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2011%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20The%20Amazon%20Appstore%20for%20Google's%20Android%20is%20launched.%20It%20is%20still%20unavailable%20on%20Apple's%20iOS%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2014%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20The%20Amazon%20Echo%20is%20launched%2C%20a%20speaker%20that%20acts%20as%20a%20personal%20digital%20assistant%20powered%20by%20Alexa%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2017%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon%20acquires%20Whole%20Foods%20for%20%2413.7%20billion%2C%20its%20biggest%20acquisition%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3E2018%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Amazon's%20market%20cap%20briefly%20crosses%20the%20%241%20trillion%20mark%2C%20making%20it%2C%20at%20the%20time%2C%20only%20the%20third%20company%20to%20achieve%20that%20milestone%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Our family matters legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

Our family matters legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

500 People from Gaza enter France

115 Special programme for artists

25 Evacuation of injured and sick

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDate%20started%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202020%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Khaldoon%20Bushnaq%20and%20Tariq%20Seksek%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Abu%20Dhabi%20Global%20Market%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20HealthTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20100%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunding%20to%20date%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%2415%20million%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

GIANT REVIEW

Starring: Amir El-Masry, Pierce Brosnan

Director: Athale

Rating: 4/5

Bridgerton%20season%20three%20-%20part%20one

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirectors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EVarious%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Nicola%20Coughlan%2C%20Luke%20Newton%2C%20Jonathan%20Bailey%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E3%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The National Archives, Abu Dhabi

Founded over 50 years ago, the National Archives collects valuable historical material relating to the UAE, and is the oldest and richest archive relating to the Arabian Gulf.

Much of the material can be viewed on line at the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive - https://www.agda.ae/en

Mohammed bin Zayed Majlis

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20ASI%20(formerly%20DigestAI)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202017%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Quddus%20Pativada%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%2C%20UAE%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Artificial%20intelligence%2C%20education%20technology%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunding%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%243%20million-plus%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20GSV%20Ventures%2C%20Character%2C%20Mark%20Cuban%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

TECH%20SPECS%3A%20APPLE%20WATCH%20SERIES%208

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDisplay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2041mm%2C%20352%20x%20430%3B%2045mm%2C%20396%20x%20484%3B%20Retina%20LTPO%20OLED%2C%20up%20to%201000%20nits%2C%20always-on%3B%20Ion-X%20glass%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EProcessor%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Apple%20S8%2C%20W3%20wireless%2C%20U1%20ultra-wideband%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECapacity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2032GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMemory%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201GB%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPlatform%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20watchOS%209%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EHealth%20metrics%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%203rd-gen%20heart%20rate%20sensor%2C%20temperature%20sensing%2C%20ECG%2C%20blood%20oxygen%2C%20workouts%2C%20fall%2Fcrash%20detection%3B%20emergency%20SOS%2C%20international%20emergency%20calling%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EConnectivity%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20GPS%2FGPS%20%2B%20cellular%3B%20Wi-Fi%2C%20LTE%2C%20Bluetooth%205.3%2C%20NFC%20(Apple%20Pay)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDurability%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20IP6X%2C%20water%20resistant%20up%20to%2050m%2C%20dust%20resistant%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBattery%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20308mAh%20Li-ion%2C%20up%20to%2018h%2C%20wireless%20charging%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECards%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20eSIM%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFinishes%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Aluminium%20%E2%80%93%20midnight%2C%20Product%20Red%2C%20silver%2C%20starlight%3B%20stainless%20steel%20%E2%80%93%20gold%2C%20graphite%2C%20silver%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EIn%20the%20box%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Watch%20Series%208%2C%20magnetic-to-USB-C%20charging%20cable%2C%20band%2Floop%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Starts%20at%20Dh1%2C599%20(41mm)%20%2F%20Dh1%2C999%20(45mm)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Result

Tottenhan Hotspur 2 Roma 3

Tottenham: Winks 87', Janssen 90 1'

Roma 3

D Perotti 13' (pen), C Under 70', M Tumminello 90 2"

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Alaan%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202021%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Parthi%20Duraisamy%20and%20Karun%20Kurien%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20FinTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%247%20million%20raised%20in%20total%20%E2%80%94%20%242.5%20million%20in%20a%20seed%20round%20and%20%244.5%20million%20in%20a%20pre-series%20A%20round%3Cbr%3E%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Rocketman

Director: Dexter Fletcher

Starring: Taron Egerton, Richard Madden, Jamie Bell

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

The biog

Hobby: "It is not really a hobby but I am very curious person. I love reading and spend hours on research."

Favourite author: Malcom Gladwell

Favourite travel destination: "Antigua in the Caribbean because I have emotional attachment to it. It is where I got married."

The Beach Bum

Director: Harmony Korine

Stars: Matthew McConaughey, Isla Fisher, Snoop Dogg

Two stars

Sole survivors

- Cecelia Crocker was on board Northwest Airlines Flight 255 in 1987 when it crashed in Detroit, killing 154 people, including her parents and brother. The plane had hit a light pole on take off

- George Lamson Jr, from Minnesota, was on a Galaxy Airlines flight that crashed in Reno in 1985, killing 68 people. His entire seat was launched out of the plane

- Bahia Bakari, then 12, survived when a Yemenia Airways flight crashed near the Comoros in 2009, killing 152. She was found clinging to wreckage after floating in the ocean for 13 hours.

- Jim Polehinke was the co-pilot and sole survivor of a 2006 Comair flight that crashed in Lexington, Kentucky, killing 49.

Specs

Engine: Duel electric motors

Power: 659hp

Torque: 1075Nm

On sale: Available for pre-order now

Price: On request

Bio

Born in Dubai in 1994

Her father is a retired Emirati police officer and her mother is originally from Kuwait

She Graduated from the American University of Sharjah in 2015 and is currently working on her Masters in Communication from the University of Sharjah.

Her favourite film is Pacific Rim, directed by Guillermo del Toro

Ferrari 12Cilindri specs

Engine: naturally aspirated 6.5-liter V12

Power: 819hp

Torque: 678Nm at 7,250rpm

Price: From Dh1,700,000

Available: Now

GAC GS8 Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 248hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 400Nm at 1,750-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 9.1L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh149,900

German intelligence warnings

- 2002: "Hezbollah supporters feared becoming a target of security services because of the effects of [9/11] ... discussions on Hezbollah policy moved from mosques into smaller circles in private homes." Supporters in Germany: 800

- 2013: "Financial and logistical support from Germany for Hezbollah in Lebanon supports the armed struggle against Israel ... Hezbollah supporters in Germany hold back from actions that would gain publicity." Supporters in Germany: 950

- 2023: "It must be reckoned with that Hezbollah will continue to plan terrorist actions outside the Middle East against Israel or Israeli interests." Supporters in Germany: 1,250

Source: Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

Email sent to Uber team from chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi

From: Dara

To: Team@

Date: March 25, 2019 at 11:45pm PT

Subj: Accelerating in the Middle East

Five years ago, Uber launched in the Middle East. It was the start of an incredible journey, with millions of riders and drivers finding new ways to move and work in a dynamic region that’s become so important to Uber. Now Pakistan is one of our fastest-growing markets in the world, women are driving with Uber across Saudi Arabia, and we chose Cairo to launch our first Uber Bus product late last year.

Today we are taking the next step in this journey—well, it’s more like a leap, and a big one: in a few minutes, we’ll announce that we’ve agreed to acquire Careem. Importantly, we intend to operate Careem independently, under the leadership of co-founder and current CEO Mudassir Sheikha. I’ve gotten to know both co-founders, Mudassir and Magnus Olsson, and what they have built is truly extraordinary. They are first-class entrepreneurs who share our platform vision and, like us, have launched a wide range of products—from digital payments to food delivery—to serve consumers.

I expect many of you will ask how we arrived at this structure, meaning allowing Careem to maintain an independent brand and operate separately. After careful consideration, we decided that this framework has the advantage of letting us build new products and try new ideas across not one, but two, strong brands, with strong operators within each. Over time, by integrating parts of our networks, we can operate more efficiently, achieve even lower wait times, expand new products like high-capacity vehicles and payments, and quicken the already remarkable pace of innovation in the region.

This acquisition is subject to regulatory approval in various countries, which we don’t expect before Q1 2020. Until then, nothing changes. And since both companies will continue to largely operate separately after the acquisition, very little will change in either teams’ day-to-day operations post-close. Today’s news is a testament to the incredible business our team has worked so hard to build.

It’s a great day for the Middle East, for the region’s thriving tech sector, for Careem, and for Uber.

Uber on,

Dara

How to apply for a drone permit

- Individuals must register on UAE Drone app or website using their UAE Pass

- Add all their personal details, including name, nationality, passport number, Emiratis ID, email and phone number

- Upload the training certificate from a centre accredited by the GCAA

- Submit their request

What are the regulations?

- Fly it within visual line of sight

- Never over populated areas

- Ensure maximum flying height of 400 feet (122 metres) above ground level is not crossed

- Users must avoid flying over restricted areas listed on the UAE Drone app

- Only fly the drone during the day, and never at night

- Should have a live feed of the drone flight

- Drones must weigh 5 kg or less

More from Neighbourhood Watch

PROFILE OF HALAN

Started: November 2017

Founders: Mounir Nakhla, Ahmed Mohsen and Mohamed Aboulnaga

Based: Cairo, Egypt

Sector: transport and logistics

Size: 150 employees

Investment: approximately $8 million

Investors include: Singapore’s Battery Road Digital Holdings, Egypt’s Algebra Ventures, Uber co-founder and former CTO Oscar Salazar

DIVINE%20INTERVENTOIN

%3Cp%3EStarring%3A%20Elia%20Suleiman%2C%20Manal%20Khader%2C%20Amer%20Daher%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Elia%20Suleiman%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%204.5%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs

- Engine: 3.9-litre twin-turbo V8

- Power: 640hp

- Torque: 760nm

- On sale: 2026

- Price: Not announced yet

Where to apply

Applicants should send their completed applications - CV, covering letter, sample(s) of your work, letter of recommendation - to Nick March, Assistant Editor in Chief at The National and UAE programme administrator for the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism, by 5pm on April 30, 2020.

Please send applications to nmarch@thenational.ae and please mark the subject line as “Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism (UAE programme application)”.

The local advisory board will consider all applications and will interview a short list of candidates in Abu Dhabi in June 2020. Successful candidates will be informed before July 30, 2020.

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

The Laughing Apple

Yusuf/Cat Stevens

(Verve Decca Crossover)