An exhibition that explores the way Pakistani art and architecture has transformed over eight decades has opened in Qatar. Although it “can't cover everything”, it also chronicles how the country has changed from the 1940s to today.

“We've tried to touch on moments – socially, politically, historically, culturally – that seemed significant and have affected the artistic and architectural language over time,” explains co-curator Zarmeene Shah.

The exhibition – Manzar: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today – brings together more than 200 artworks, photos, sculptures, videos and installations to explore how the country's rich cultural landscape has shifted over time. Through archival material and newly commissioned works by artists and architects living and working in the country and its diaspora, Manzar seeks to shine a light on underrepresented creative movements.

Running until January 31 at the National Museum of Qatar in Doha, the show organised by Art Mill Museum – which is under construction and is due to open in 2030 – opened on Friday during a week-long launch of artistic events in the country.

It has been co-curated by Caroline Hancock, Art Mill Museum's senior curator of modern and contemporary art; Aurelien Lemonier, Art Mill Museum's curator of architecture, design and gardens; and Shah, an independent curator, writer and director of graduate studies at Karachi’s Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture.

“The title, Manzar, is primarily thought of as an Urdu word but it’s also an Arabic and Farsi word, so it has a larger relationship to the region and to where this exhibition takes place,” Shah tells The National. “It means, broadly, ‘a view, a scene, a perspective, a landscape’. We deploy it in the singular, very deliberately, to say that it is one view, one perspective of many possible. The show spans 80 years of a country's history, so it would be impossible to cover everything.

“We hope that it will open up ways of questioning, seeing and relating to how artistic and creative expression has unfolded across Pakistan.”

The large-scale exhibition extends from the museum’s gallery spaces to the courtyard of the Palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, offering a broad immersion in Pakistani art and architecture and scenography designed by renowned architect Raza Ali Dada.

It is laid out chronologically in tandem with significant political and social events to help contextualise the creative shifts that take place and unfolds across 12 sections. Topics include aesthetic experiments; calligraphy; nation-building; regionalism; neo-miniatures; the urban vernacular; and the politics of land and water.

Newspaper clippings, posters and archives lent by public institutions, like the Alhamra Art Museum in Lahore and Pakistan National Council of the Arts in Islamabad, complements each chapter.

The exhibition begins in the years before the partition of the subcontinent in 1947, which marked the creation of Pakistan and India, following the transition and social upheaval that the divide formed. The withdrawal of the British occupation was followed by a violent split in the new country, with East Pakistan later becoming Bangladesh in 1971.

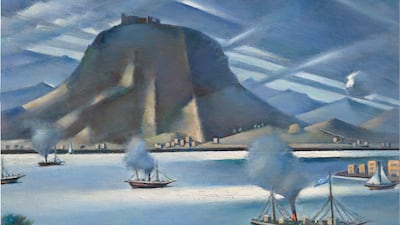

There are works by pre-partition masters such as Ustad Allah Bakhsh and Abdur Rahman Chughtai, whose work was rooted in narratives of land and people, and Bangladeshi artists Zainul Abedin, whose work in the 1950s reflected the effect of colonisation on the region.

“The 50s and 60s are quite important in the development of both artistic and architectural languages, because artists were travelling across the world, encountering European and American modernist movements and then coming back to think about how it works within their own context and developing their own language,” adds Shah.

“Even within architecture, they were looking at climate, looking at where they were and how that works, and developed realistic and brutalist architecture which we can see in the works of architects like Yasmeen Lari and Habib Fida Ali.”

Other sections focus on the experiments with nation-building and the reinterpretation of traditional Mughal miniatures, eventually reaching a time in the 1990s and 2000s when the urban language began to change, often referred to as 'Karachi Pop'.

Pakistani artist Aisha Khalid’s work with neo-miniatures are part of the show. The three pieces represent her early career. “In my work, I have reimagined and expanded the traditional miniature technique to convey a contemporary narrative, transforming it into a mode of self-expression that speaks to the modern world,” Khalid says. “Over time, my approach to this medium has evolved, moving from small-scale, intimate pieces to more expansive, large-scale paintings."

The vibrant port city of Karachi, known as Pakistan’s economic and financial capital, also developed a distinct pop art movement with a different aesthetic to the western version. Artists like Iftikhar, Elizabeth Dadi, David Alesworth and Durriya Kazi began to explore art forms that referenced folklore, pop culture and craftsmanship.

The exhibitions's final section returns to the beginning, focusing on land, water and people. It reflects the climate change problem facing the world today. In three commissioned installations in the palace courtyard, architect Yasmeen Lari and the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan showcase pavilion-like bamboo shelters which have been developed as emergency housing for flood victims.

The pavilion covered with indigo-dyed textiles brings together heritage, architecture, art and ecology summarises what the exhibition is all about.

Manzar: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today runs until January 31 at The National Museum of Qatar in Doha